Commentary

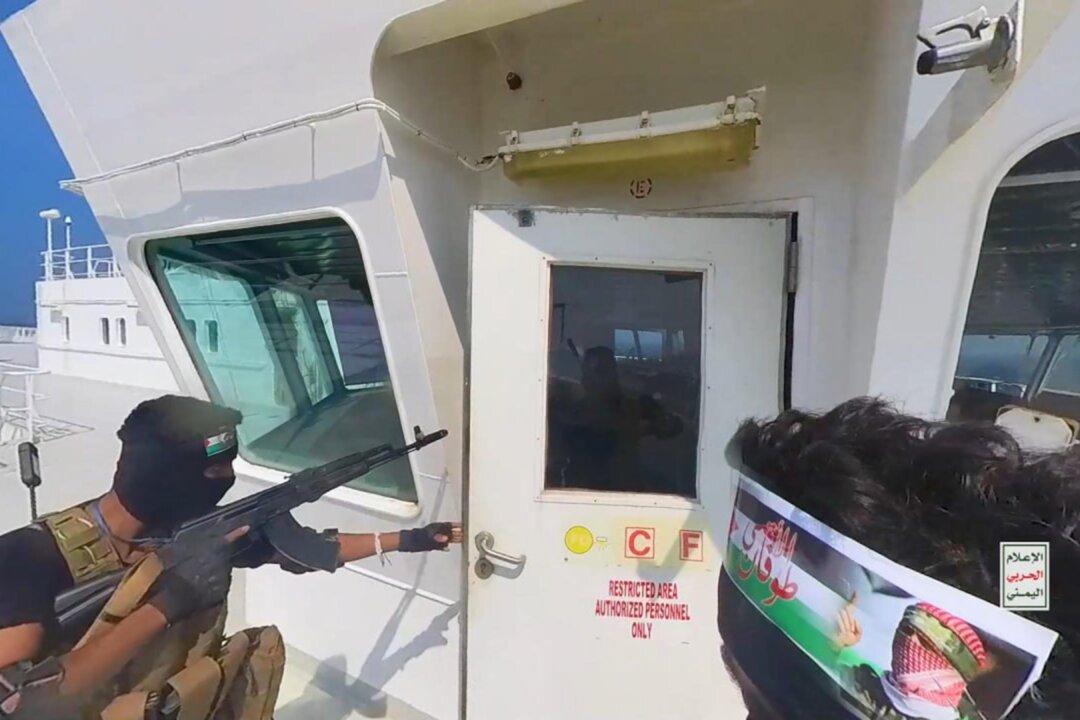

Insurance companies have a profound impact on strategic outcomes, as Houthi attacks in the Red and Arabian Seas in November and December demonstrated.

Insurance companies have a profound impact on strategic outcomes, as Houthi attacks in the Red and Arabian Seas in November and December demonstrated.