Commentary

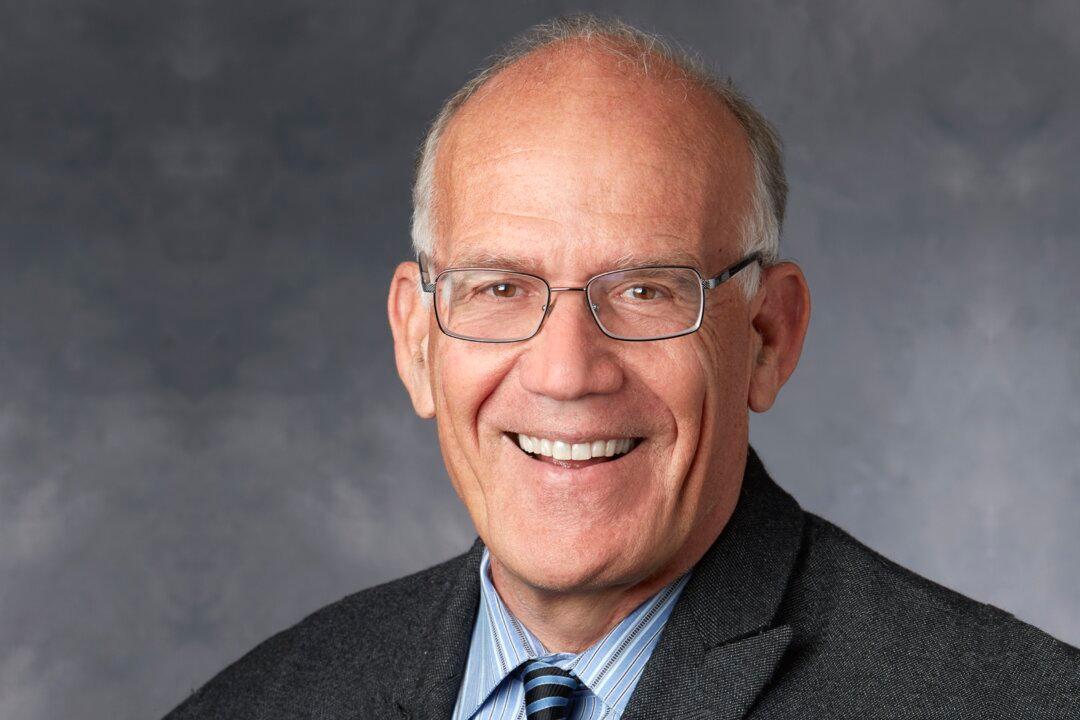

Victor Davis Hanson’s latest book, “The Dying Citizen: How Progressive Elites, Tribalism, and Globalization are Destroying the Idea of America,” is a prescient account of how the American conceptualization of citizenship has been eroded by progressive ideologues and those who wish to undermine the original intent of the Framers. He focuses on the categories of pre-citizens and post-citizens.