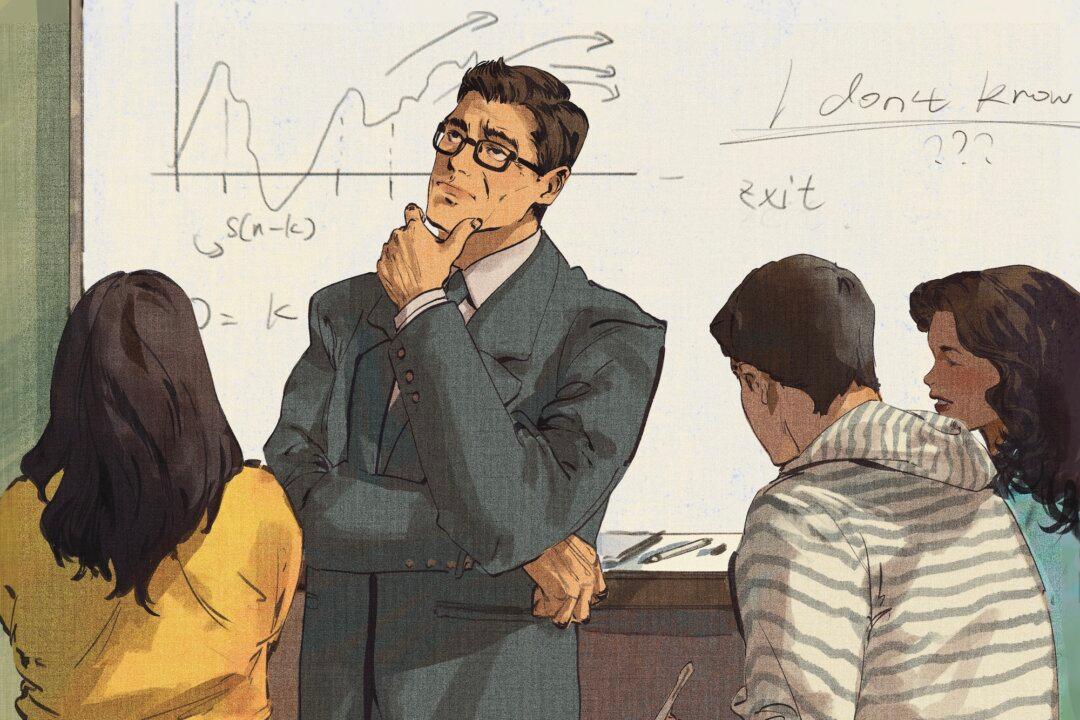

Three valuable words I learned early on in my teaching days were “I don’t know.”

When a Latin student asked me why a certain phrase in the “Aeneid” was in the ablative absolute or a kid in World History wondered why Hindus revered cows, my standard response to such questions for which I hadn’t a clue was always “I don’t know, but I’ll look it up and tell you next time.” Students recognize that bluster and baloney are a camouflage for ignorance, and their reaction is justifiable contempt, but, like the rest of us, they respect honesty.