Commentary

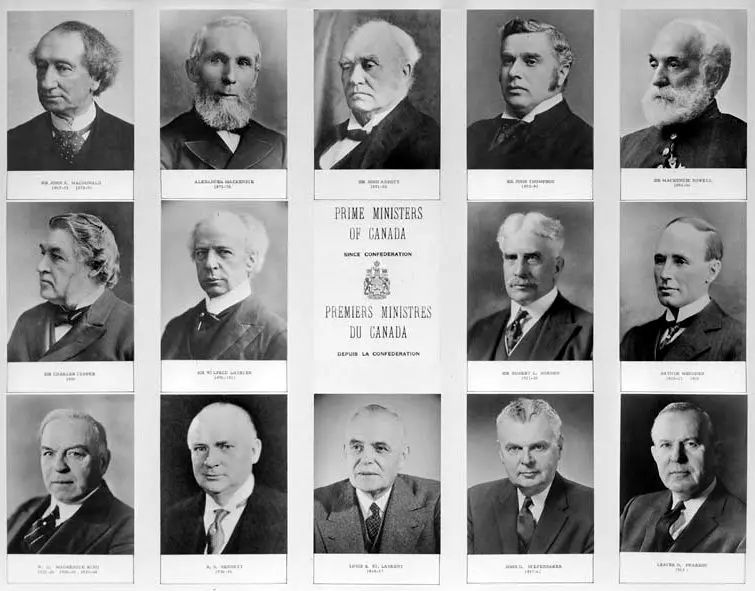

On the evening of Oct. 22, 1962, President John F. Kennedy made a dramatic appearance on television to announce that the Soviet Union had taken the intolerable step of installing offensive missiles in Cuba, just 90 miles from the mainland United States. Kennedy’s appearance was followed shortly after 8 p.m. by Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, speaking in the traditional setting, the House of Commons.