Commentary

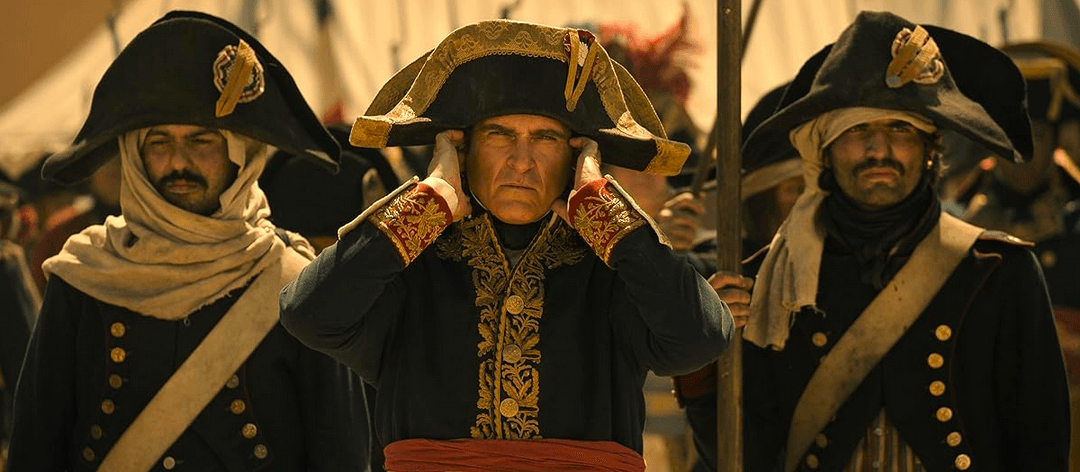

The new Ridley Scott movie “Napoleon” is good, not great. It at least provides a tantalizing overview of post-revolutionary France about which most Americans today know absolutely nothing. It does put on screen the astounding brutality of old-world forms of warfare and their complete disregard for the human life of the people on the frontlines. So that’s something.