Commentary

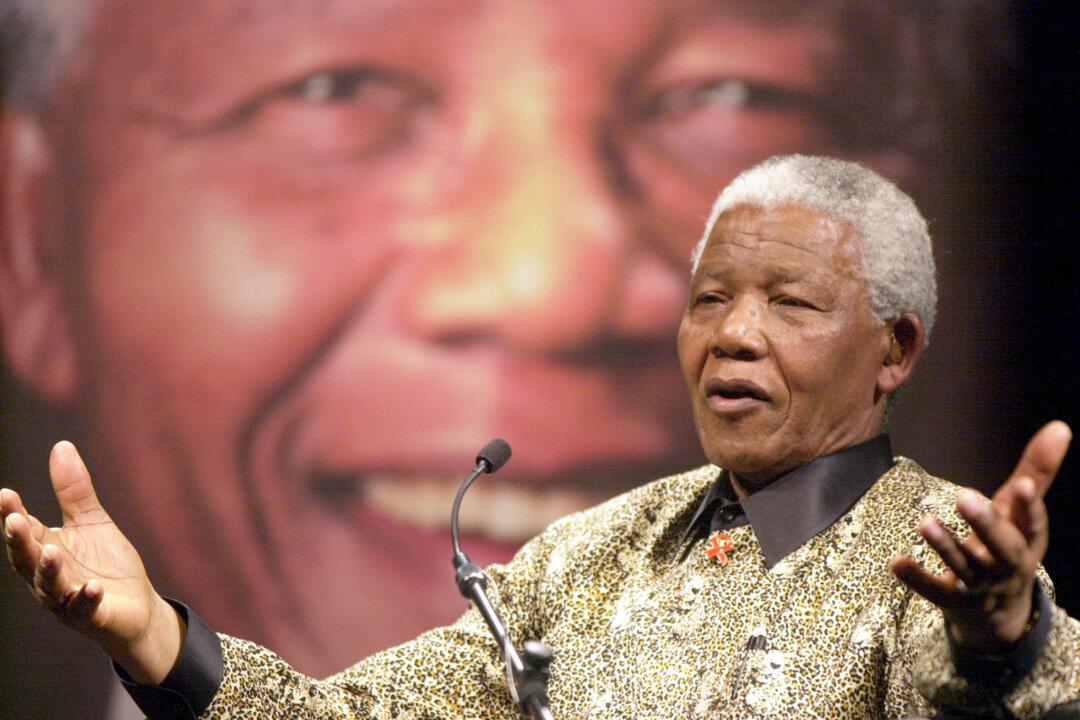

The death of South Africa’s last president before the end of the apartheid era gives reason to pause and reflect on the historic transfer of power from Frederick Willem de Klerk to Nelson Mandela 27 years ago.

The death of South Africa’s last president before the end of the apartheid era gives reason to pause and reflect on the historic transfer of power from Frederick Willem de Klerk to Nelson Mandela 27 years ago.