Commentary

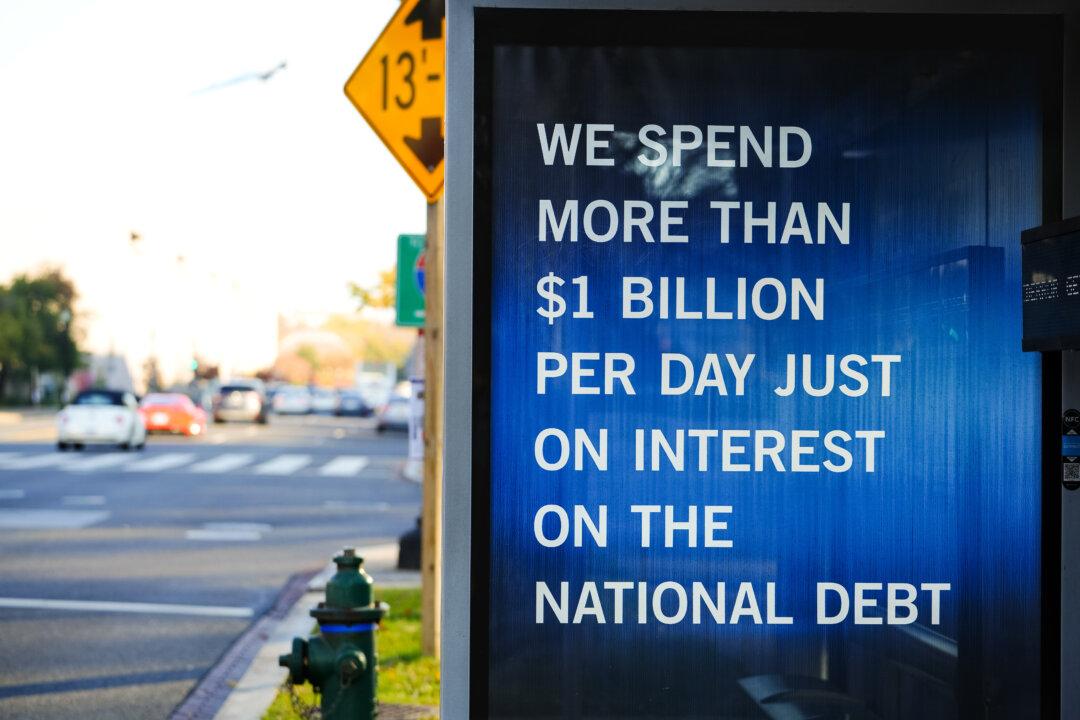

Our country’s Founders abhorred government debt. In his Farewell Address, George Washington urged future congresses and presidents to avoid “the accumulation of debt, not only by shunning occasions of expense, but by vigorous exertion in time of peace to discharge the debts, which unavoidable wars may have occasioned, not ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burden, which we ourselves ought to bear.”