Commentary

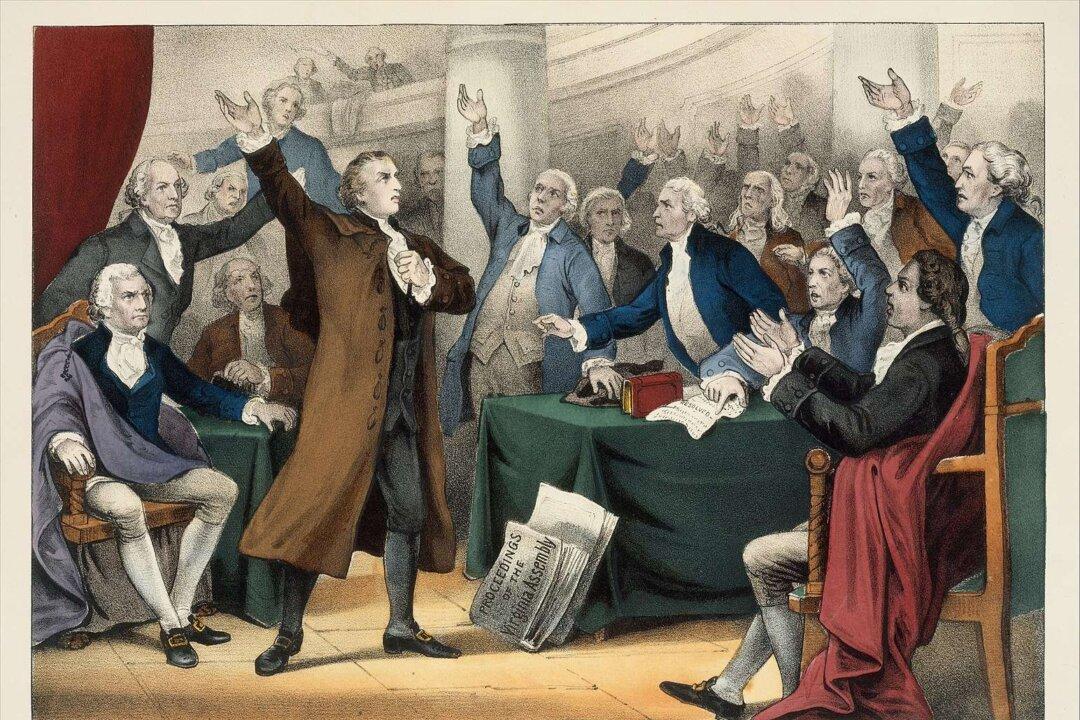

In St. John’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia, delegates from around the colony gathered to discuss matters that would rile Britain’s distant king and set Virginia on a path to rebellion. The date was March 23, 1775.

In St. John’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia, delegates from around the colony gathered to discuss matters that would rile Britain’s distant king and set Virginia on a path to rebellion. The date was March 23, 1775.