Commentary

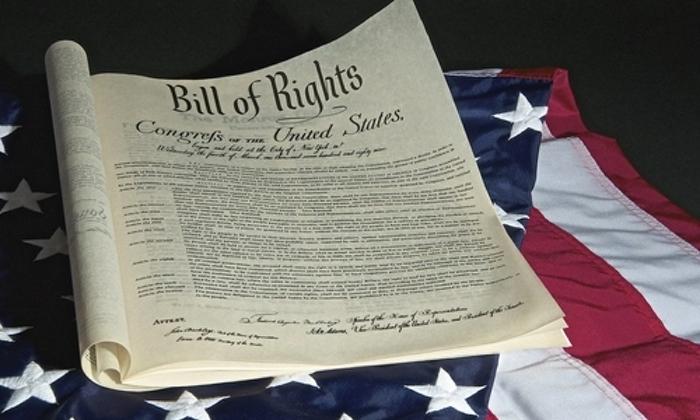

Bill of Rights Day is this Friday (Dec. 15). The Bill of Rights explicitly recognizes our rights to freedom of press, speech, and religion; the right to bear arms; to have a trial by jury; and for all government functions not enumerated in the Constitution to be reserved for the people and the states.