Commentary

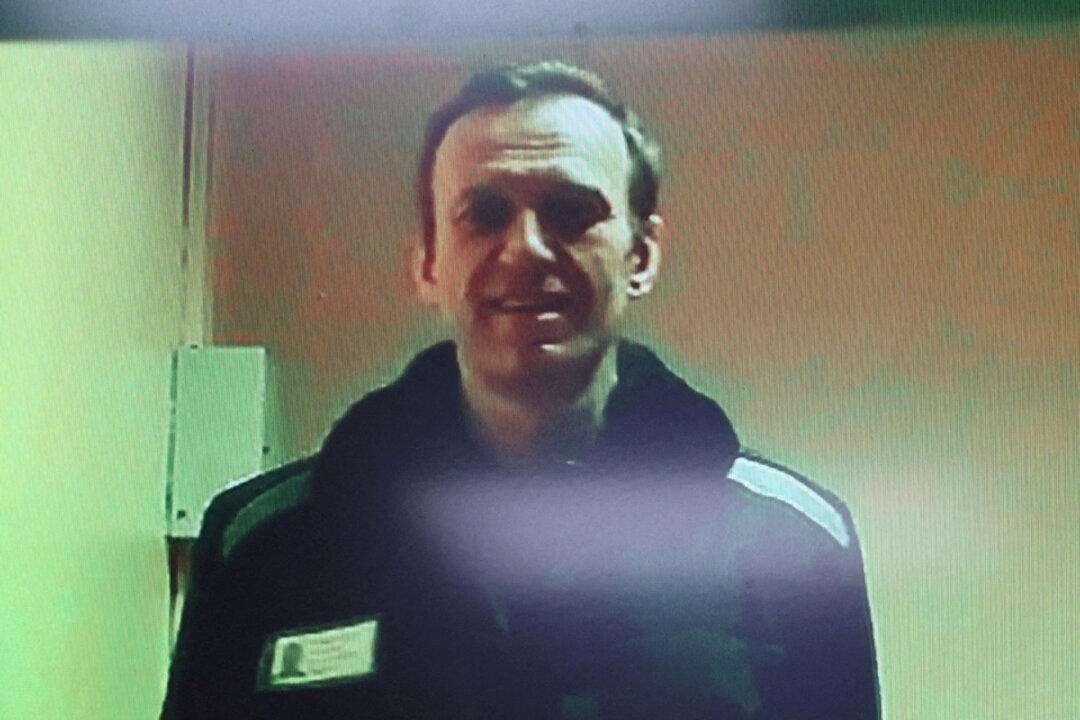

Russian political activist and dissident Alexei Navalny died on Feb. 16 in a Siberian prison camp, where he was serving a 30-year sentence for what most observers agree were specious, purely politically motivated convictions.

Russian political activist and dissident Alexei Navalny died on Feb. 16 in a Siberian prison camp, where he was serving a 30-year sentence for what most observers agree were specious, purely politically motivated convictions.