Commentary

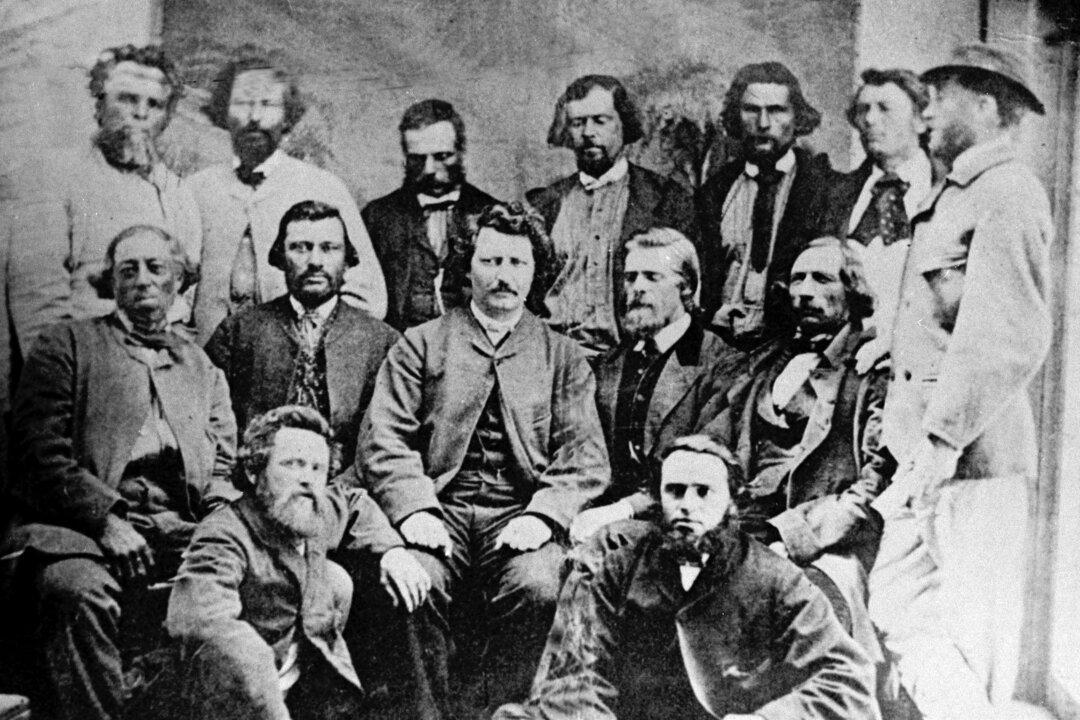

Since 1866, Irish nationalists in the United States had been launching cross-border attacks into Canada hoping that military success in that British territory would lead, somehow, to an end to the occupation of Ireland.

Since 1866, Irish nationalists in the United States had been launching cross-border attacks into Canada hoping that military success in that British territory would lead, somehow, to an end to the occupation of Ireland.