Commentary

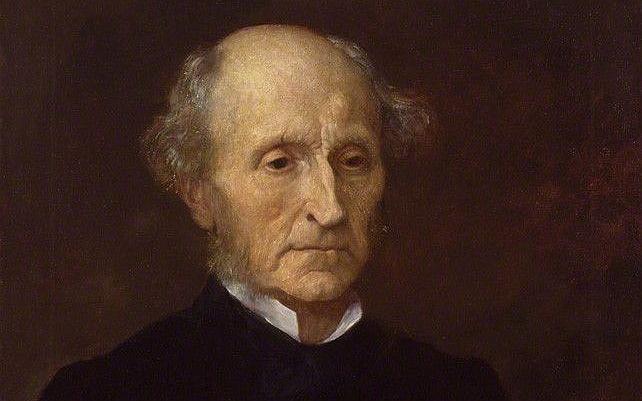

It was in a philosophy class that I first read John Stuart Mill’s Essay “On Liberty,” which spends so much time on the idea of free speech: It is not for views that are popular and approved but rather unpopular and unapproved. We need it because we lack access to certain truths, and so all claims need to be constantly tested. Further, the sheer size of anything resembling truth is so vast that everyone needs freedom to express in order to get closer to the whole.