Commentary

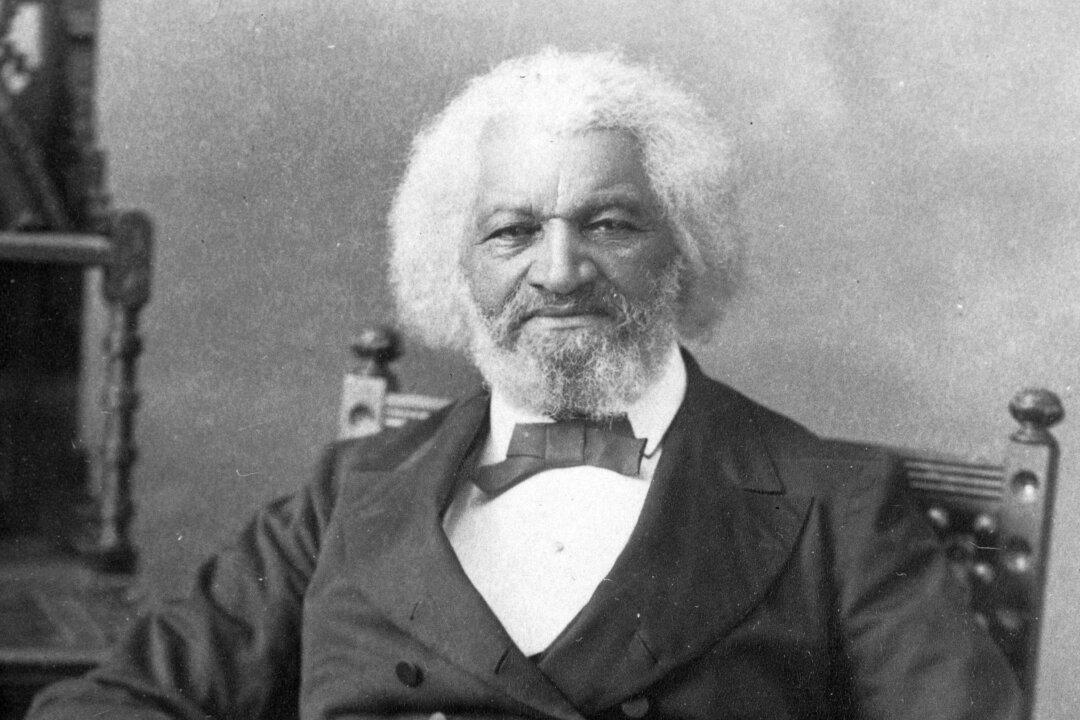

Mark Twain copied a friend’s remark into his notebook: “I am not an American; I am the American.” That is a claim—to be the American, the exemplary or representative American—that very few Americans could plausibly make. Twain himself could. Benjamin Franklin could and did. Abraham Lincoln could but didn’t, though admirers made the claim for him. Surely some number of others could, too. But among all Americans past or present, no one could make such a claim more compellingly than Frederick Douglass.