Commentary

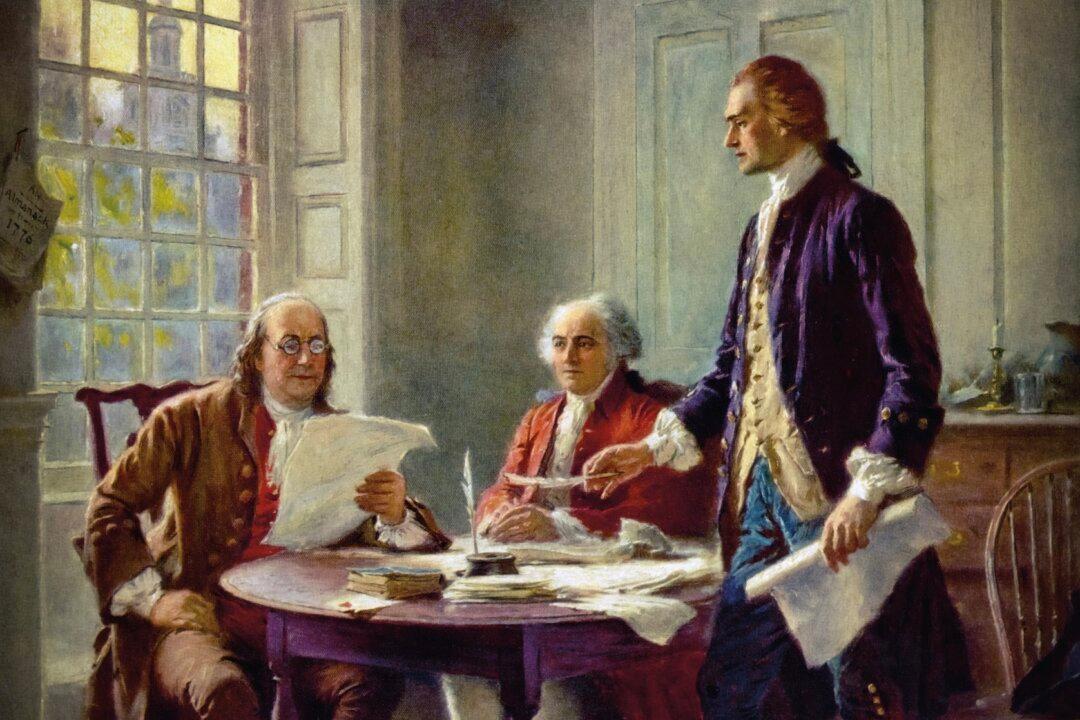

When the American founders separated from the political control of Britain, they might have simply said, “We are done with your annoying colonialism.” Instead, Thomas Jefferson set out to write a manifesto that struck at the very heart of all political systems, laying out a theory that would change all of human history. His words still echo today and serve as the benchmark for what is considered liberty, justice, and the good society.