Commentary

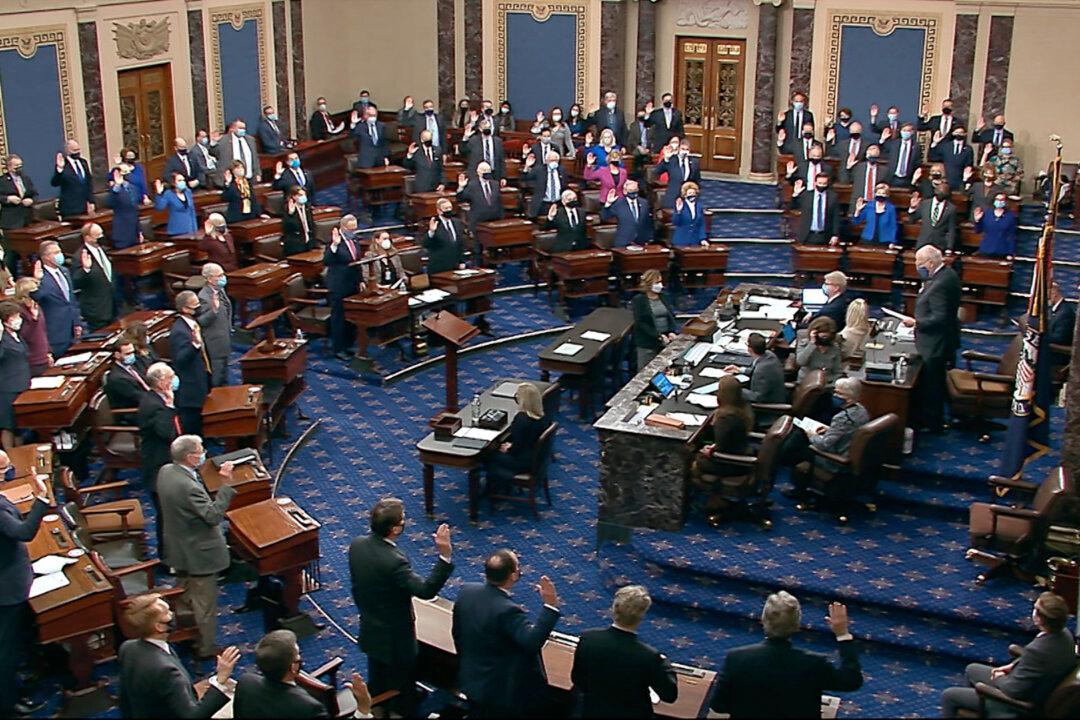

Does the U.S. Senate have jurisdiction to try former President Donald Trump? There’s no shortage of absolute yes and no answers floating around the media.

Does the U.S. Senate have jurisdiction to try former President Donald Trump? There’s no shortage of absolute yes and no answers floating around the media.