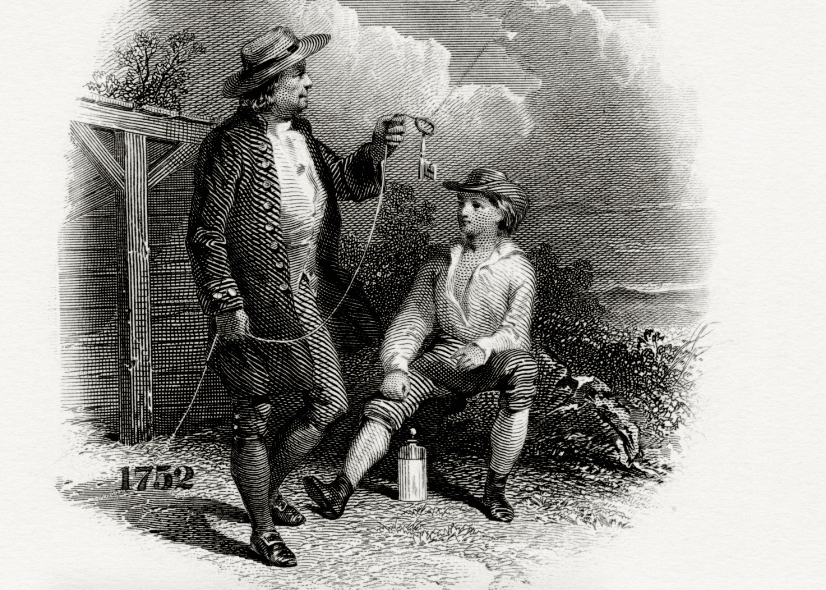

Benjamin Franklin’s words about diligence appeared in his “Poor Richard’s Almanac,” which he issued annually for 25 years. Almanacs were popular among 18th-century readers, and this enterprise proved his greatest commercial success. But it wasn’t just “Poor Richard’s Almanac” that brought Franklin wealth and fame.

It was, in fact, diligence.