Following decades of oppression, on Aug. 25, insurgents of the Muslim Rohingya minority attacked Myanmar police at 30 of their posts across Rakhine state under the banner of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, which emerged during the past year and is funded from Saudi Arabia. The attacks unleashed a horrific response from the military and forced about 420,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh.

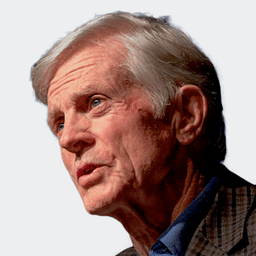

The Swedish journalist and author Bertil Lintner, who has been writing about Burma/Myanmar and Asia for nearly four decades, wrote later in the Asia Times: