Commentary

Viewpoints

Opinion

Cultural Revolution 1966 v. 2020

Part 1: The start of the Cultural Revolution in China

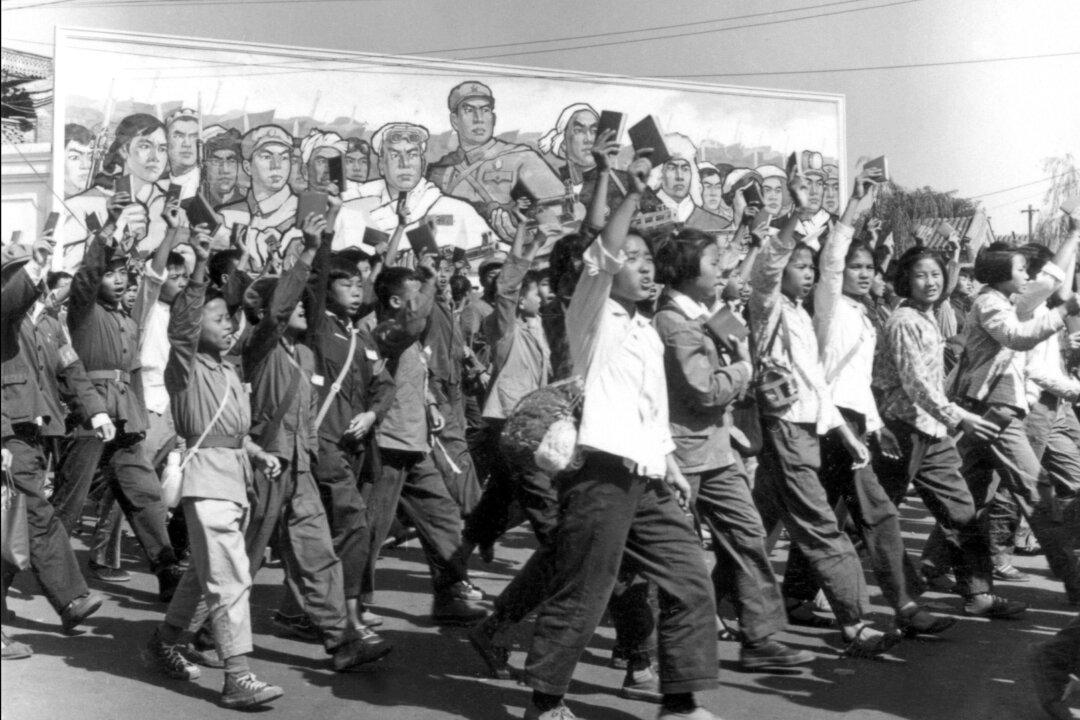

Red Guard members wave copies of Chairman Mao’s “Little Red Book” during a parade in Beijing in June 1966. Young people are easily manipulated, and when they act in concert for what they believe are good causes, those causes often end up in disaster and mass violence. Jean Vincent/AFP via Getty Images

David Kopel

Contributor

|Updated: