News analysis

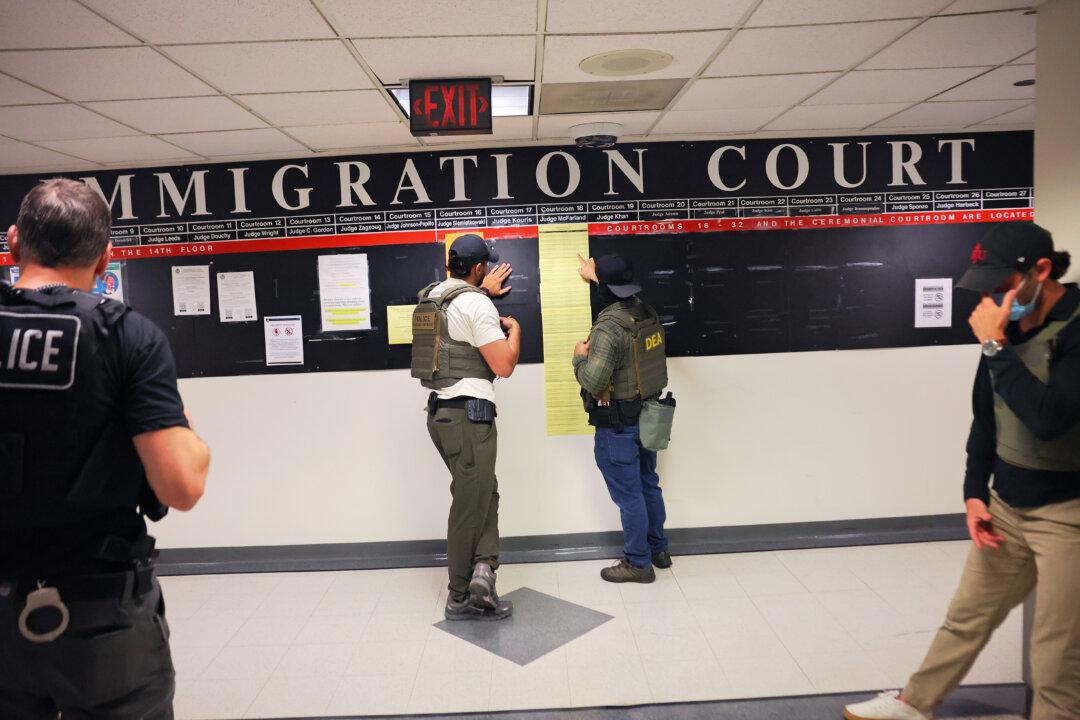

New migrants pouring into the United States after the Biden administration let a COVID-19 restriction called Title 42 expire last week will not break the nation’s stretched court system. The system is already shattered, according to several former judges, immigration experts, and Department of Homeland Security data.