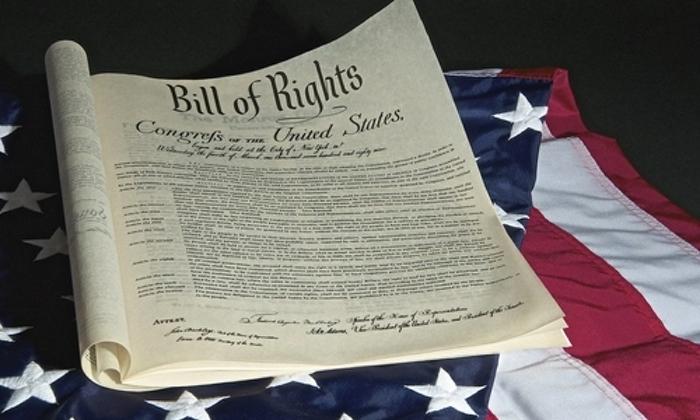

In honor of U.S. Constitution Day, on Sept. 17, we present a five-part series on the Bill of Rights. It reveals how the first 10 amendments to the Constitution guarantee freedom of speech, religion, and the press, and, in so many other ways, limit the power of the federal government and secure the rights of individuals.

Thomas Jefferson said: “When governments fear the people, there is liberty. When people fear the government, there is tyranny.”