Commentary

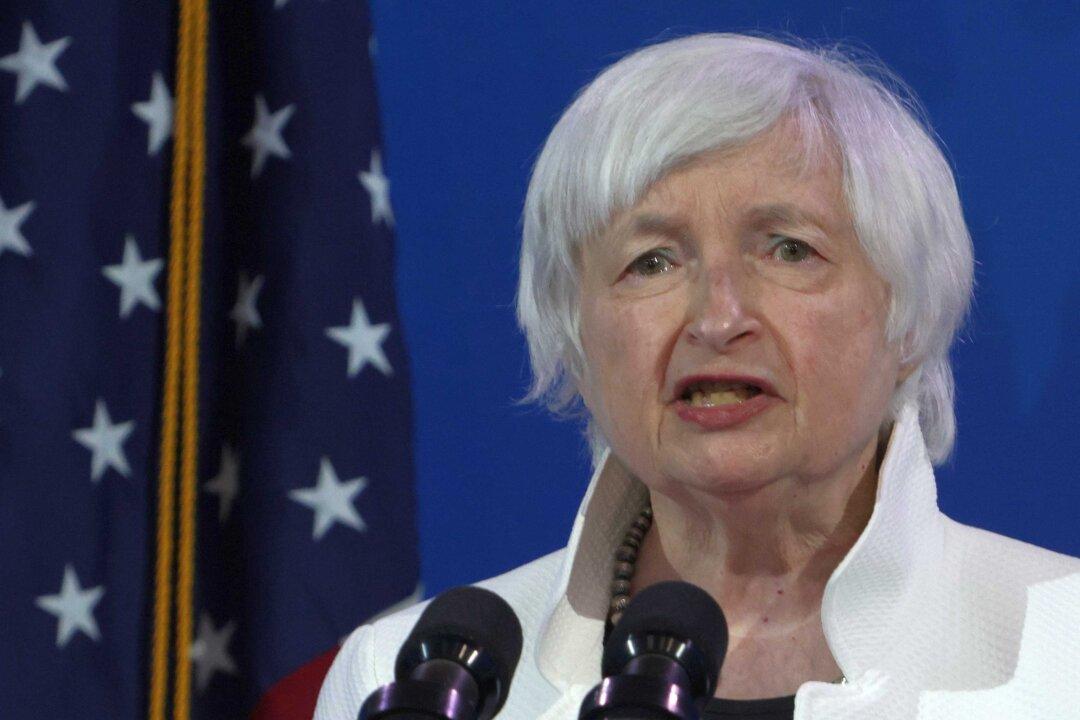

Shortly before her nomination as Treasury secretary in the Biden administration, Janet Yellen appeared on a Bloomberg New Economy panel discussing the role of central banks as the world struggles to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic. The panel revealed a sharp difference of opinion between Yellen and one of her predecessors—Larry Summers, President Bill Clinton’s second Treasury secretary.