Commentary

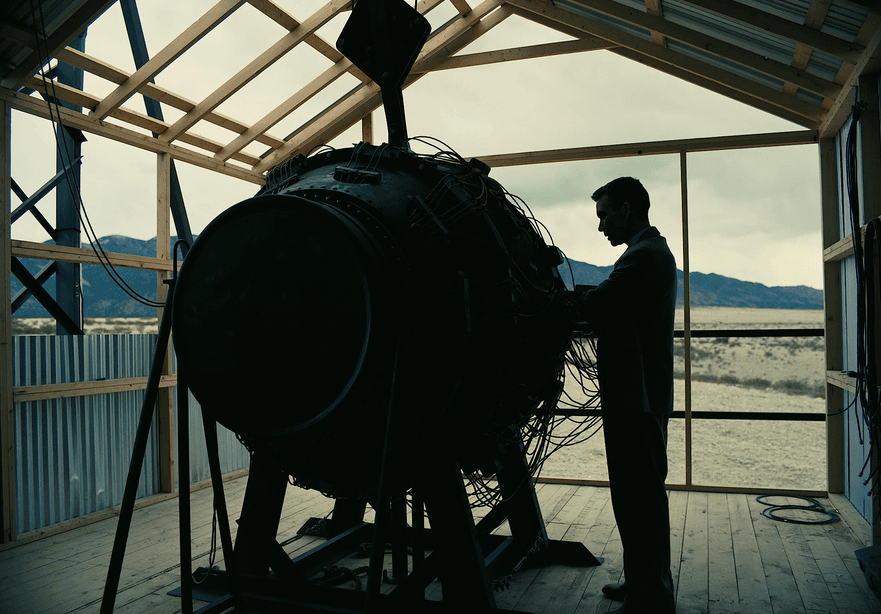

Christopher Nolan’s film “Oppenheimer” has sparked a good deal of debate. Some support the proposition that Mr. Nolan did a great job of storytelling and accurately relating historical truths. On the other hand, many critics appear to be disturbed by their perception that Mr. Nolan didn’t sufficiently demonize the development and use of atomic weaponry.