Commentary

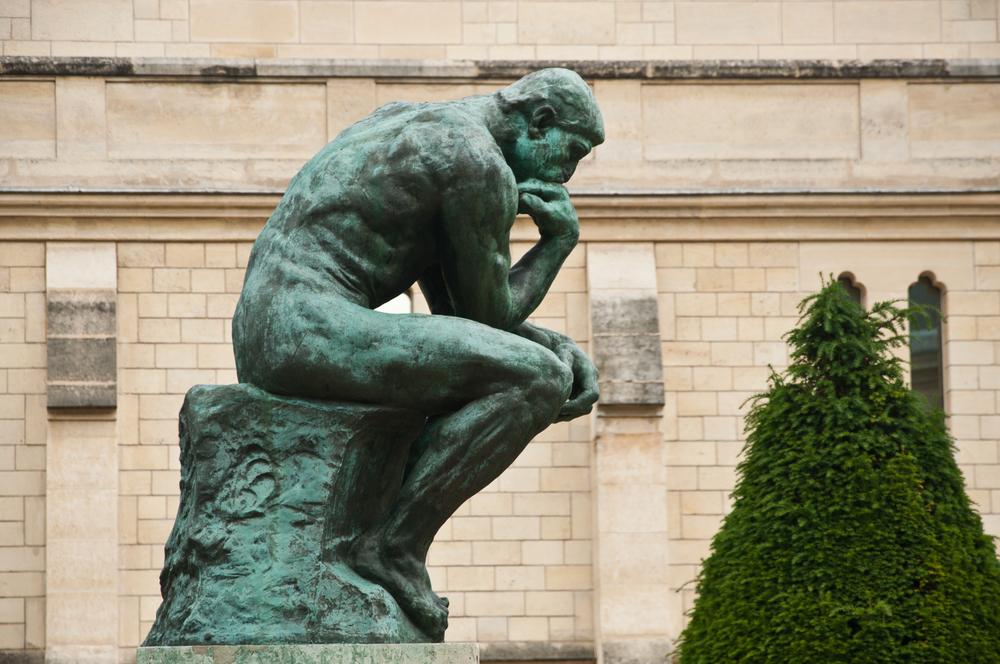

It is somewhat unsettling to discover that no matter how fervently we believe in something, others believe differently. Perhaps more frustratingly, we soon discover that our interlocutors are as passionate about their beliefs as we are about ours and have sound reasons for believing as they do.