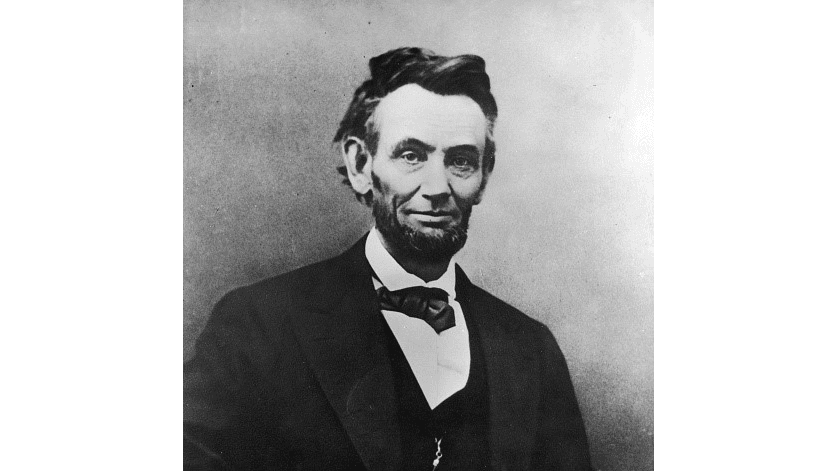

Editor’s note: The following is the third in a series of excerpts from “A Horse for Mr. Lincoln” by the Hon. Preston Manning, a self-described “lifelong fan of Lincoln.” Illustrated by Henri de Groot, the book is a work of fiction and looks at how events in the United States might have turned out differently, with the country being much more unified today if Abraham Lincoln had not gone to the theatre on that fateful night of April 14, 1865.

A little-known Illinois country attorney, Abraham Lincoln, was seeking the Republican nomination for president as shown in “The Lincoln Miracle: Inside the Republican Convention That Changed History” by Edward Achorn. Public Domain

Preston Manning served as a member of the Canadian Parliament from 1993 to 2001, and as leader of the Opposition from 1997 to 2000. He founded two political parties: the Reform Party of Canada and the Canadian Reform Conservative Alliance. Both of these became the Official Opposition in Parliament and led to the creation of the Conservative Party of Canada, which formed the federal government from 2004–2015.

Author’s Selected Articles