Commentary

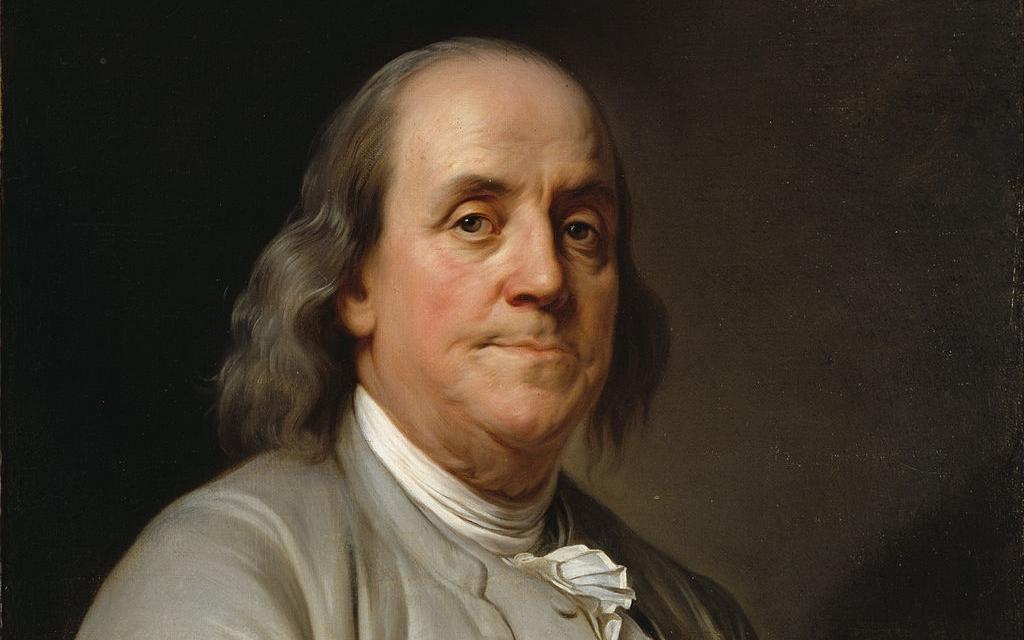

It is only natural that a conversation about an autobiography turns to a conversation about vanity. After all, who writes a book about himself?

It is only natural that a conversation about an autobiography turns to a conversation about vanity. After all, who writes a book about himself?