Commentary

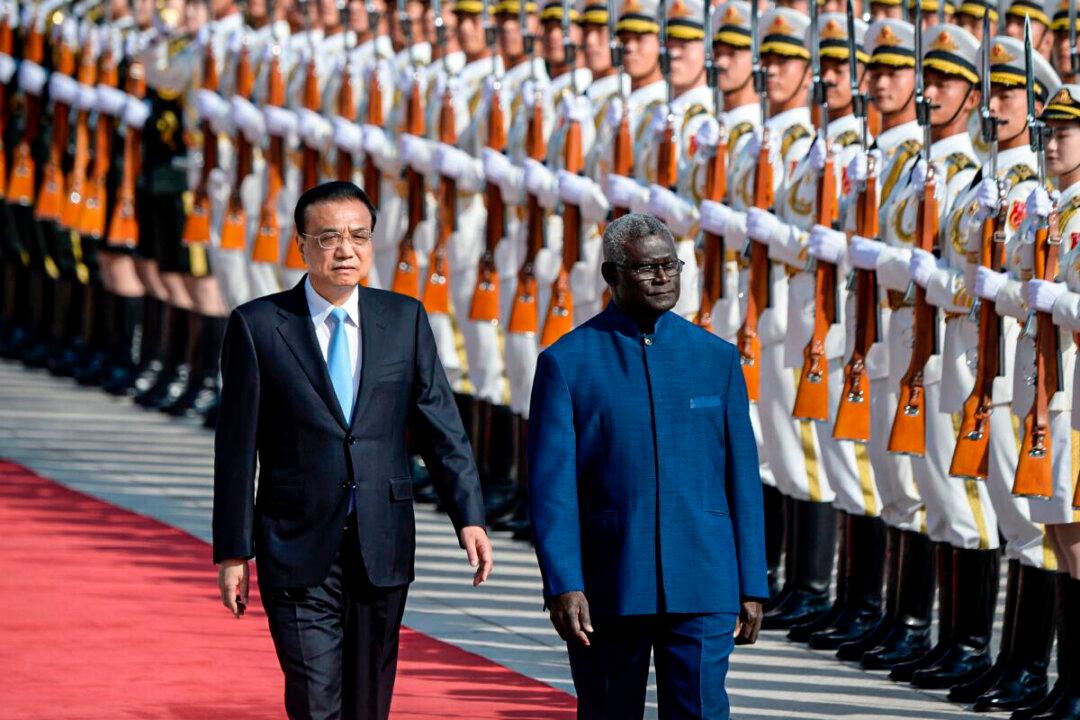

On March 24, a leaked draft agreement between the Solomon Islands and the People’s Republic of China on security cooperation sent shockwaves through the Australian political and security establishments.

On March 24, a leaked draft agreement between the Solomon Islands and the People’s Republic of China on security cooperation sent shockwaves through the Australian political and security establishments.