Commentary

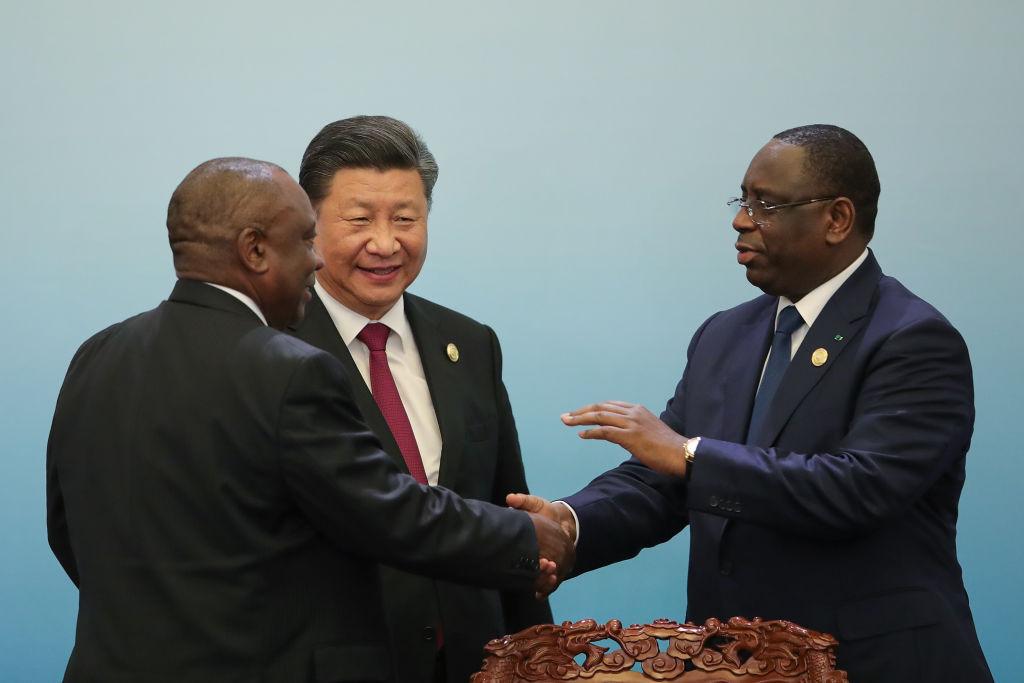

Beijing has Africa in its sights because the continent has the resources it needs to realize its great power ambitions. Consequently, huge energy has been invested into growing the Belt and Road Initiative’s (BRI) penetration into Africa.

Beijing has Africa in its sights because the continent has the resources it needs to realize its great power ambitions. Consequently, huge energy has been invested into growing the Belt and Road Initiative’s (BRI) penetration into Africa.