Commentary

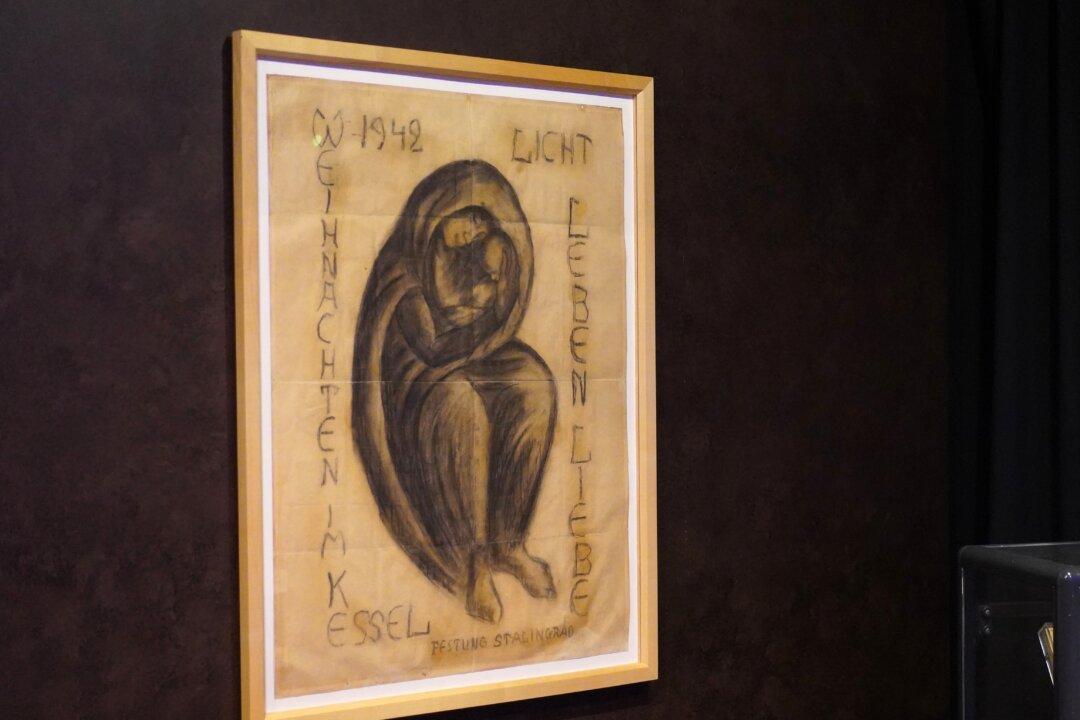

A charcoal drawing of the Madonna and child by a German pastor during the Battle of Stalingrad at Christmas in 1942 was meant to mark the festive season, but his artwork was suppressed by the Nazis.

A charcoal drawing of the Madonna and child by a German pastor during the Battle of Stalingrad at Christmas in 1942 was meant to mark the festive season, but his artwork was suppressed by the Nazis.