Commentary

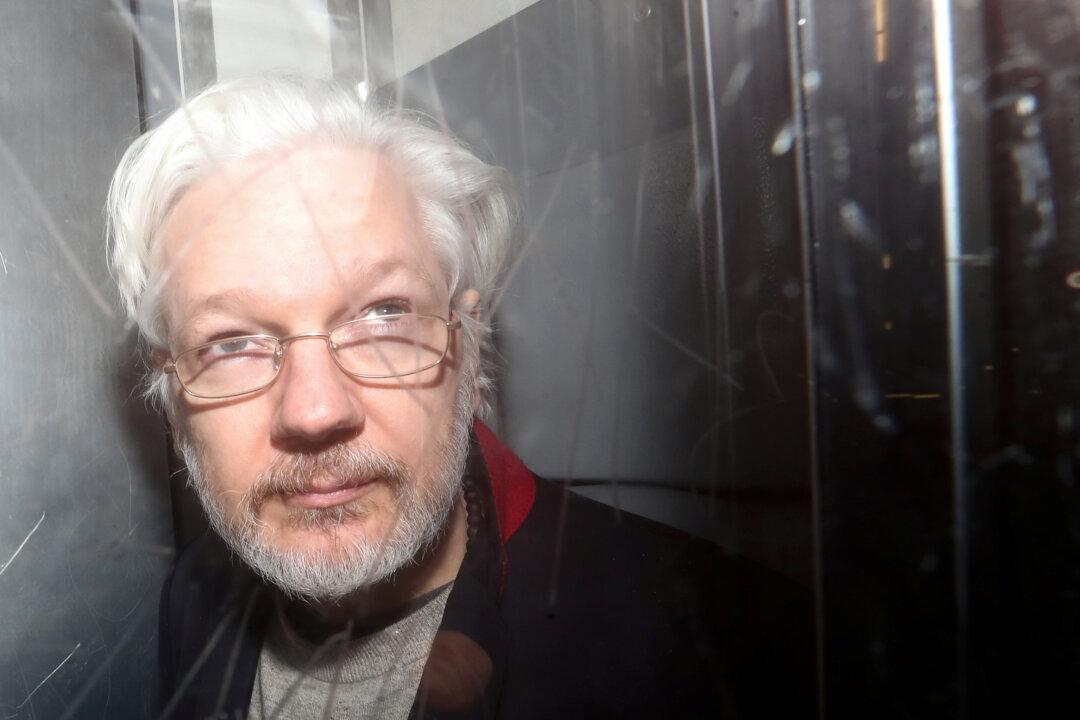

On June 17, the United Kingdom Home Secretary Priti Patel confirmed that she had approved the extradition of Julian Assange to the United States. The extradition decision has unleashed demands by protestors that Assange be freed from Belmarsh prison, where he has been kept since April 2019.