Commentary

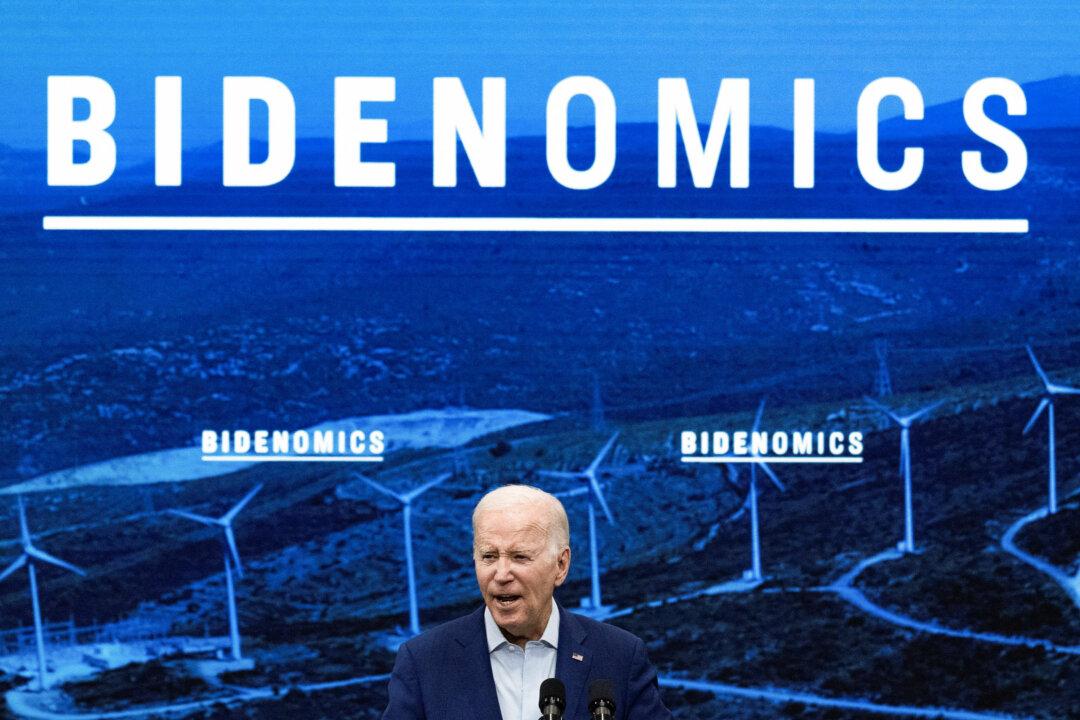

As election season approaches, Democrats are touting the economic results of Biden administration policies aimed at improving the lives of working Americans and creating a more equitable economy. But ordinary Americans aren’t feeling the so-called success of “Bidenomics.”