Commentary

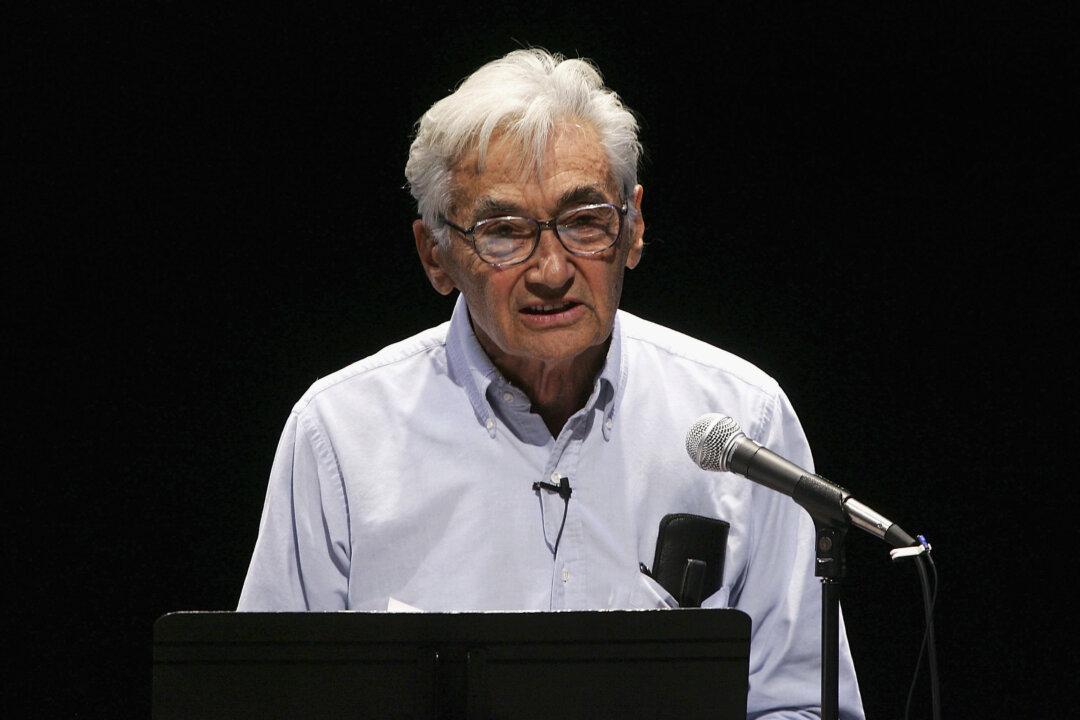

The year 2019 is closing out with the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall following shortly after the death of former Soviet dissident Vladimir Bukovsky, who wanted, but never got, a Nuremberg-style reckoning for the totalitarian regime that killed more than 10 times as many as the Nazi regime did.