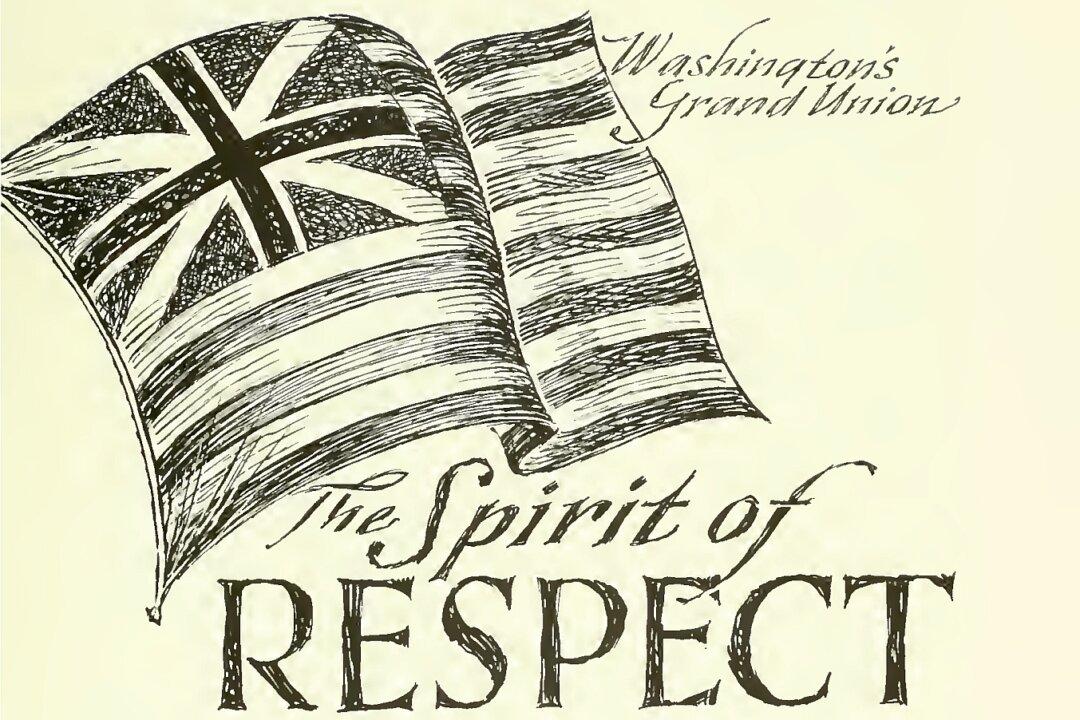

This is part one of a 10-part series of reflections on Eric Sloane’s book on the bicentennial, “The Spirits of ’76.” Each chapter covers a different spirit of America.

In 1973, as the bicentennial of the United States approached, the great American essayist and illustrator Eric Sloane was commissioned to write a book commemorating what is great about the United States. He focused on what we once had and might be losing.