Commentary

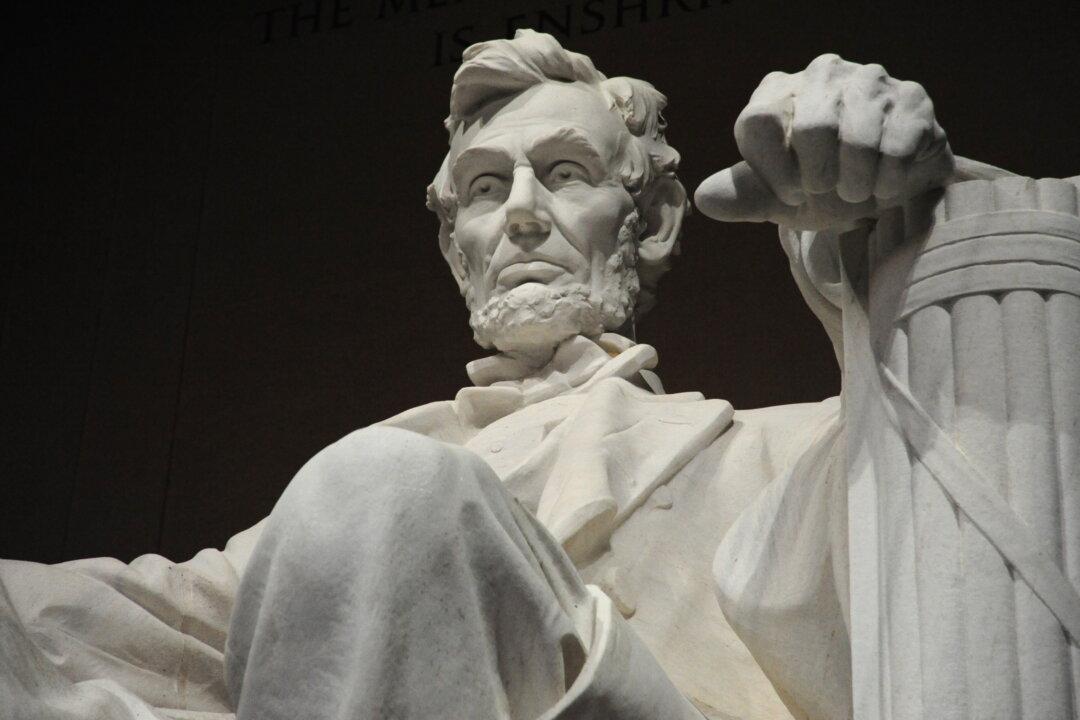

When I viewed the film, “Lincoln,” in which Daniel-Day Lewis plays President Abraham Lincoln, I noticed there were very few young people in the audience. Yet it is precisely our youth who could benefit from understanding one of the most influential figures in American history. One wonders how a humorous storyteller from such humble origins and repeated failures transformed himself into a complex and exceptional leader.