The Hong Kong government’s decision to invoke an emergency law to ban people from wearing face masks in an effort to quell ongoing protests has prompted international criticism.

Local media first revealed the government’s plans on Oct. 3, which was formally announced by Hong Kong’s top official, Chief Executive Carrie Lam, the following day.

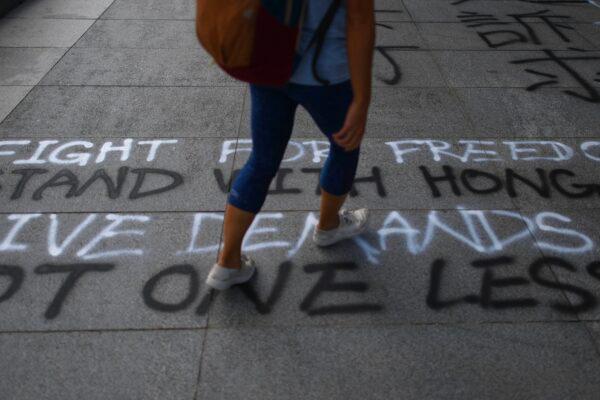

For almost four months, protesters have been marching on the streets against Beijing’s encroachment into city affairs since it reverted from British to Chinese rule. Their demands have since expanded to include calls for universal suffrage and holding the police accountable for their use of force. Face and gas masks have become a common sight during the movement, serving as a shield for protesters amid volleys of tear gas. Protesters also wish to protect their identity for fear of police or government retaliation.

Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.), meanwhile, called the measure “shameful” and “just the beginning.”

Lam invoked a colonial-era emergency law to carry out the mask ban on Oct. 4, citing “serious public danger.” The law will make it illegal for anyone to wear masks in a public gathering of over 50 people, or a demonstration with more than 30 people. Anyone who violates the law could face a one-year sentence or be subject to a HK$25,000 ($3,188) fine. The ban went into effective after midnight on Oct. 4.

China’s foreign ministry satellite office in Hong Kong welcomed the gesture, saying that the Chinese government “resolutely supports all necessary measures” Hong Kong authorities take to punish “lawbreakers and rioters.”

Chinese state media also endorsed the measure enthusiastically, saying that banning masks alone would not be enough. Beijing Daily suggested in an editorial that the Hong Kong government should clean up “Lennon Walls”—where supporters of protests leave post-it notes and posters with messages of solidarity—and regulate local media that are “reversing black and white and making things up.” It also suggested that Hong Kong authorities tighten customs control to prevent protesters from obtaining supplies.

Not Addressing the Issue

But officials from other countries disagreed with the move, with many expressing concerns that the law could drag the city deeper into the crisis.Both the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) said that banning face masks would not help quiet down the unrest in Hong Kong as Lam would hope.

Responding to the enactment of the regulation, British foriegn secretary Dominic Raab said that political dialogue was the only way forward and cautioned Hong Kong officials against aggravating tensions.

In a similar vein, spokesperson for the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Marta Hurtado said in a statement that “any restriction must have a basis in law and be proportionate and as least intrusive as possible.”

Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council, a cabinet-level government agency responsible for cross-strait relations, said that they were “seriously concerned” about the development, which could be a gateway for Hong Kong authorities to “do whatever they want.”

“When a government uses authoritarian and violent repression toward citizens, it not only cannot solve the problems, but can rip the society further apart and further distance the rulers from people,” Su Jia-chyuan, speaker of Taiwan’s unicameral legislature, said in a statement on Facebook. He said that the law would only “add fuel to the fire.”

Human rights group Amnesty International also criticized the mask ban as a “smokescreen” and “an extreme attempt to quash protests.”

Hong Kong police have so far arrested 2,119 in relation to protests and pressed charges against 409 people, according to the police’s latest figures.

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad also chimed in. He said that Lam should resign, adding that she “has to obey the masters [in Beijing] and at the same time she has to ask her conscience,” while speaking at a conference in Kuala Lumpur, according to online news portal Malaysiakini.