The number of Brits with CCP virus antibodies dropped by one quarter over a three-month period according to a large-scale study—but scientists say it doesn’t prove the case against stable natural immunity.

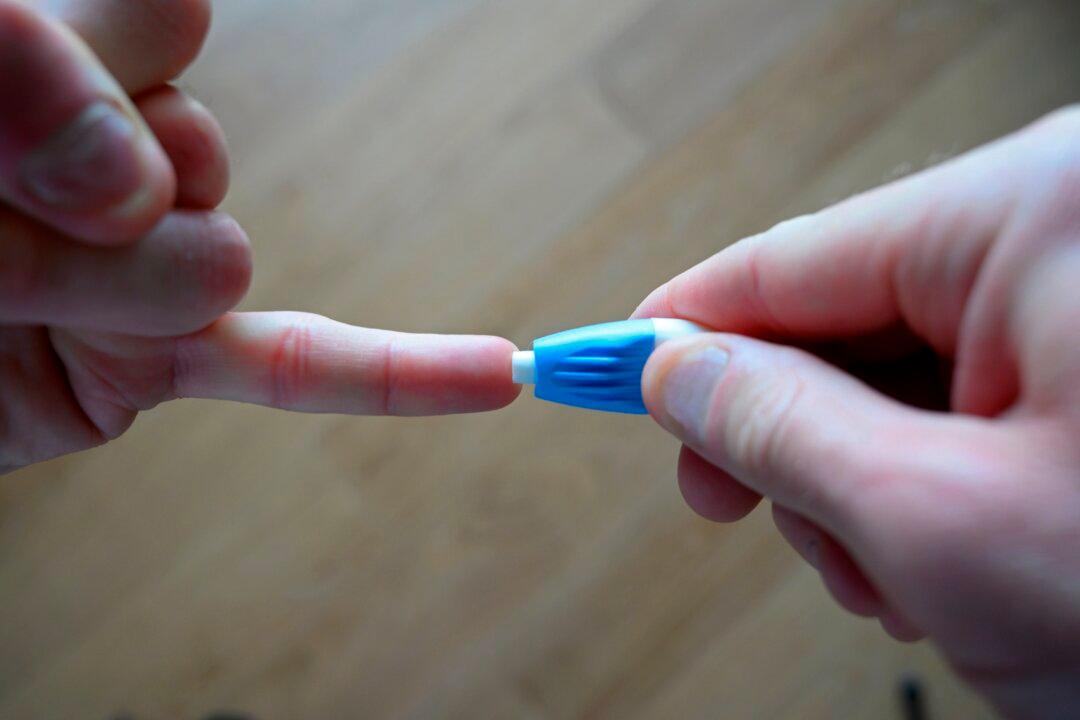

Researchers from Imperial College London used DIY finger-prick tests for antibodies on 365,000 people at home over three rounds.