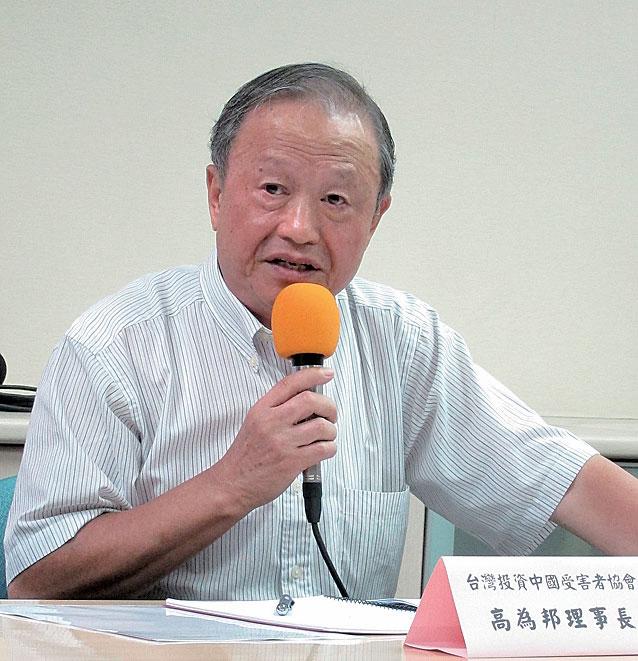

After Kao Wei-Pang came to Canada from Taiwan in the late 1960s, he completed his postdoctoral work at McGill University and went on to teach for two years at Montreal’s Vanier College.

“I have deep feelings for Canadians,” says Kao.

After Kao Wei-Pang came to Canada from Taiwan in the late 1960s, he completed his postdoctoral work at McGill University and went on to teach for two years at Montreal’s Vanier College.

“I have deep feelings for Canadians,” says Kao.