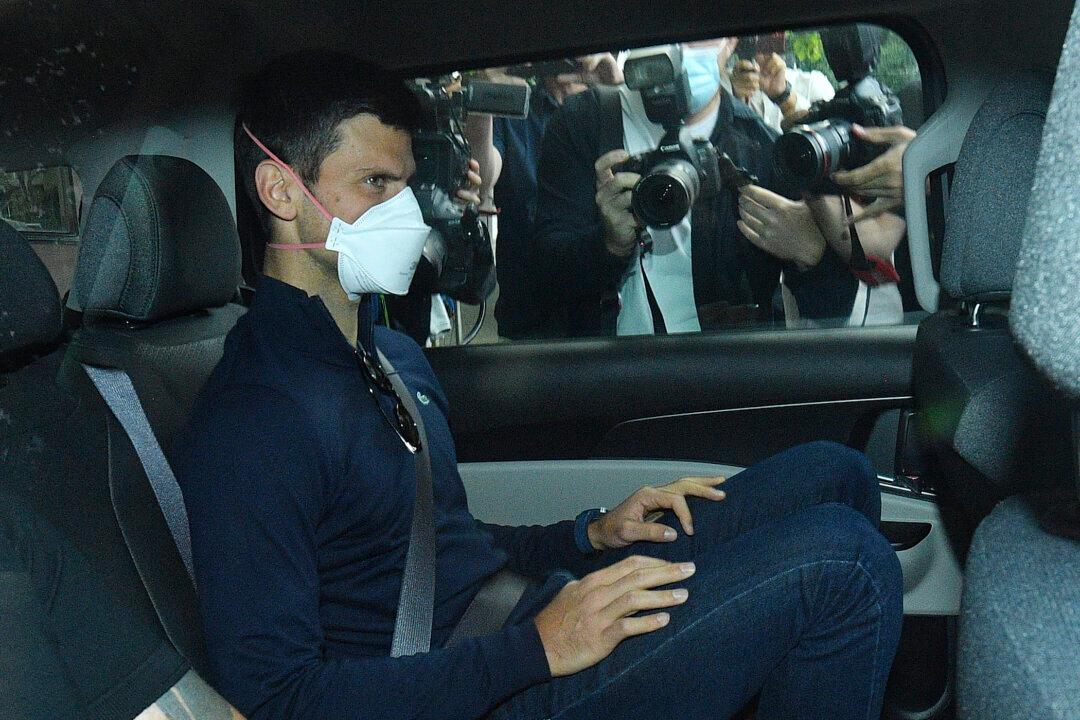

The Federal Court of Australia has revealed its reasons for dismissing Novak Djokovic’s legal challenge to his visa cancellation, which ended a week-long saga where the male world number one fought to stay on Australian shores to compete for his 21st Grand Slam.

In a unanimous decision by the full bench, Chief Justice James Allsop, and Justices Anthony Besanko and David O'Callaghan, stressed that their ruling was not about whether Djokovic would pose a risk to Australia’s health, safety, or good order, but rather about whether Immigration Minister Alex Hawke was lawful in his decision to revoke the Serbian’s visa.