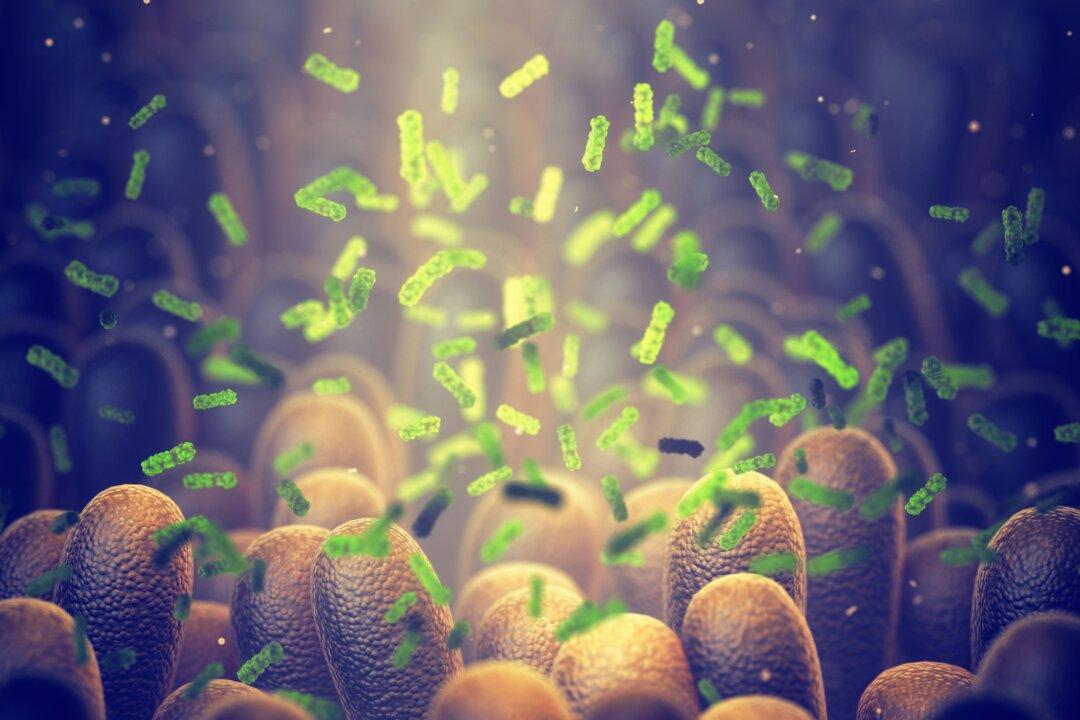

The effect of probiotics largely depends on the bacteria that are already in the stomach, researchers have discovered, through samples taken from people’s stomachs.

The researchers sought to find out how much probiotics change the composition of microbes in the stomach and what chemical compounds they produce.