The state of California is giving childhood victims of sexual abuse more time to decide if they want to file lawsuits, the latest in a growing trend among states to expand the statute of limitations in the United States.

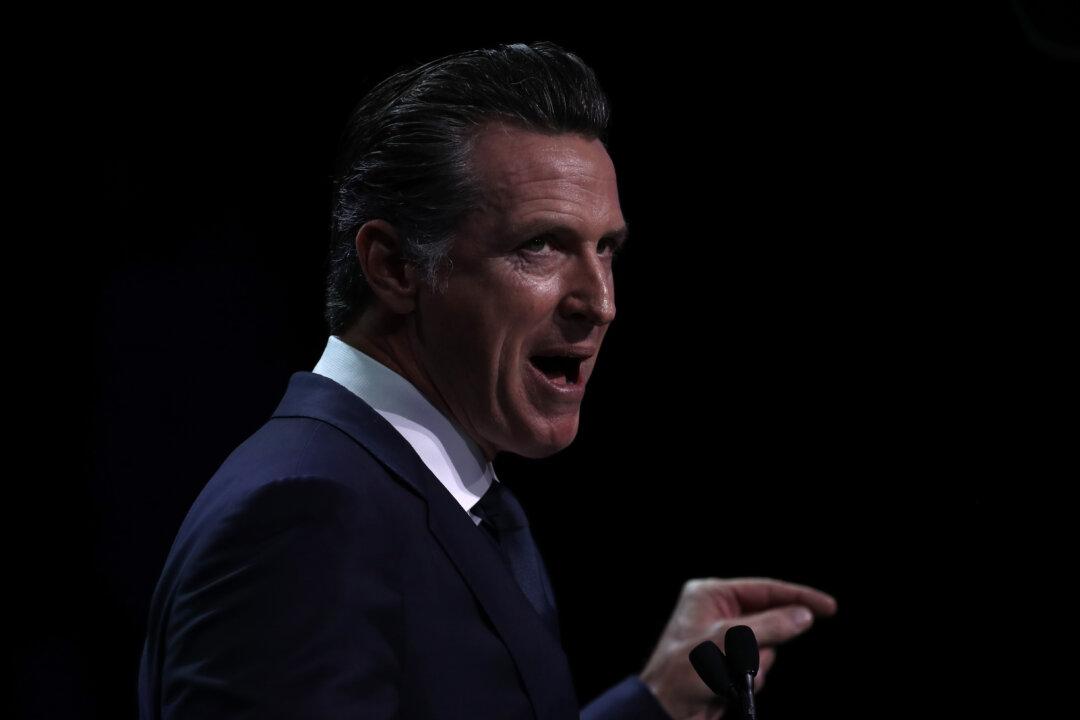

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the law into effect on Oct. 13 to give childhood sexual abuse victims until the age of 40, or five years from the discovery of the abuse, to file civil lawsuits. Previously, the limit was at 27 years old, or within three years of the discovery of the abuse.