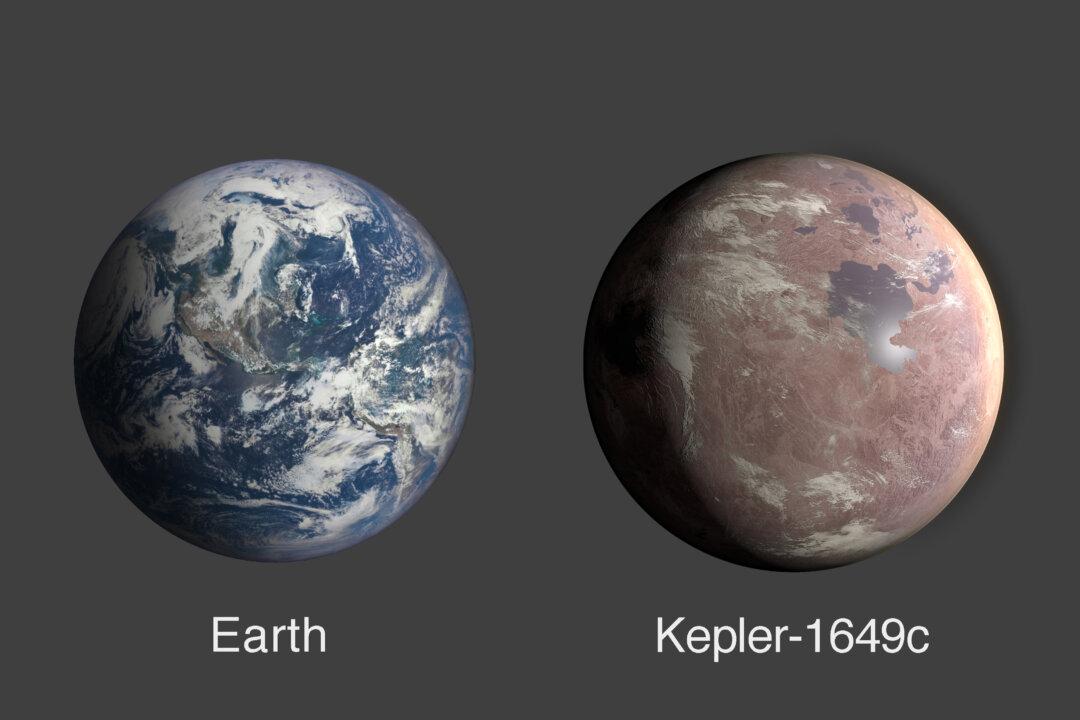

A team of transatlantic scientists taking a second look at data observations from NASA’s Kepler space telescope, which the agency retired in 2018, have discovered an earth-size exoplanet orbiting in its star’s habitable zone, the space agency announced in a press release on April 15.

The planet, called Kepler-1649c, is located 300 light-years from Earth and is most similar to it in size and estimated temperature, being just 1.06 times larger than our planet, NASA said. The amount of starlight it receives from its host star is 75 percent of the amount of light Earth receives from our sun, suggesting the exoplanet’s temperature may be similar to Earth’s too.