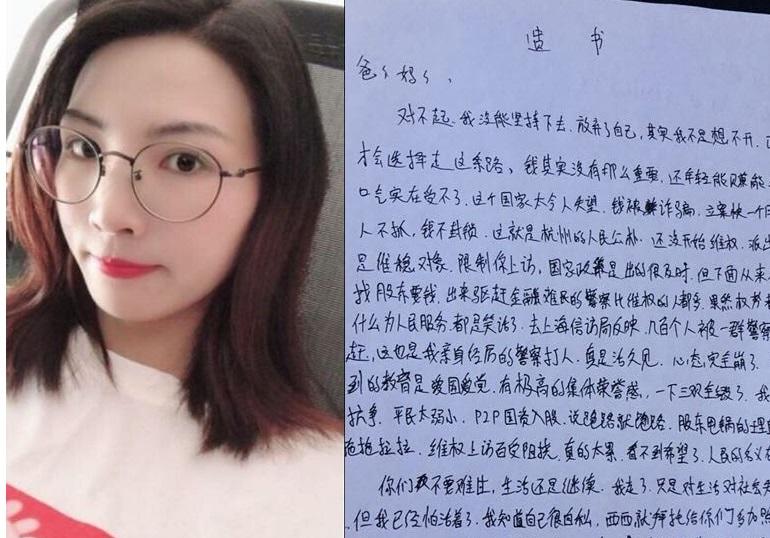

Around 4 a.m. on Sept. 7, construction workers in Jinhua, a city in eastern China’s Zhejiang Province, found the body of a woman hanging from a tree in a park. She was Wang Qian, a 31-year-old single mother who had lost her savings in China’s recent peer-to-peer (P2P) lending crash.

Wang worked as an individual seller on Taobao, a Chinese shopping site similar to eBay. She had invested her money in P2P platform PPMiao, which collapsed on Aug. 6. She lost about 260,000 yuan ($38,000).