Commentary

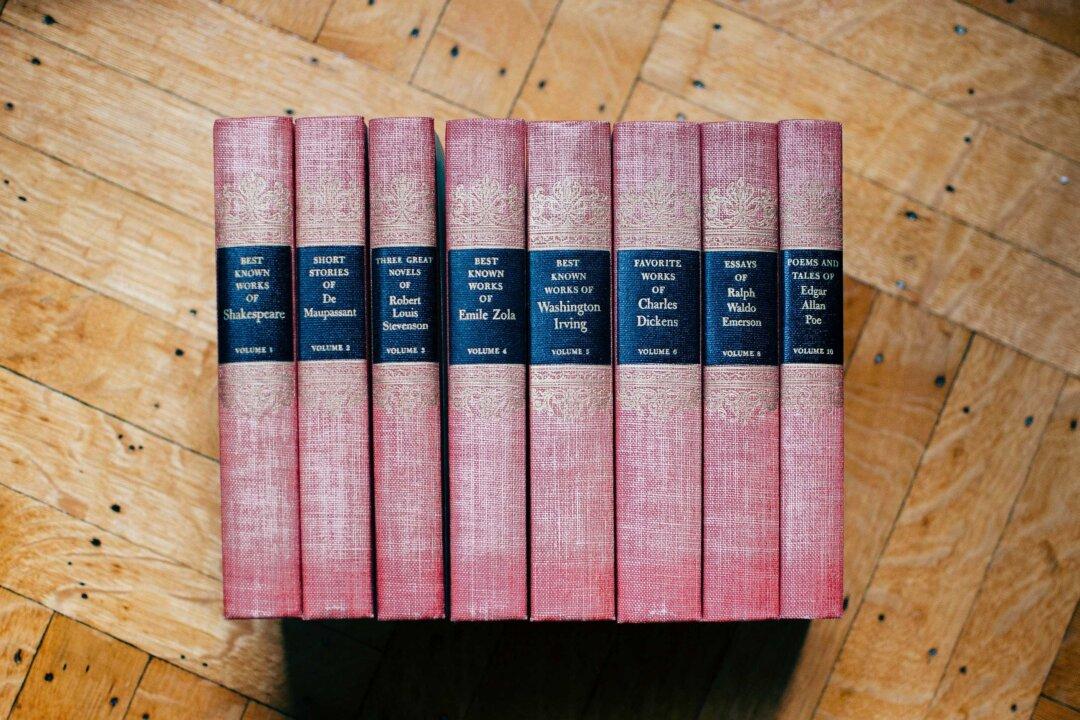

A recent article in School Library Journal (SLJ), titled “To Teach or Not to Teach: Is Shakespeare Still Relevant to Today’s Students?” reports that many English teachers want Shakespeare removed from school curricula to “make room for modern, diverse, and inclusive voices.”