News Analysis

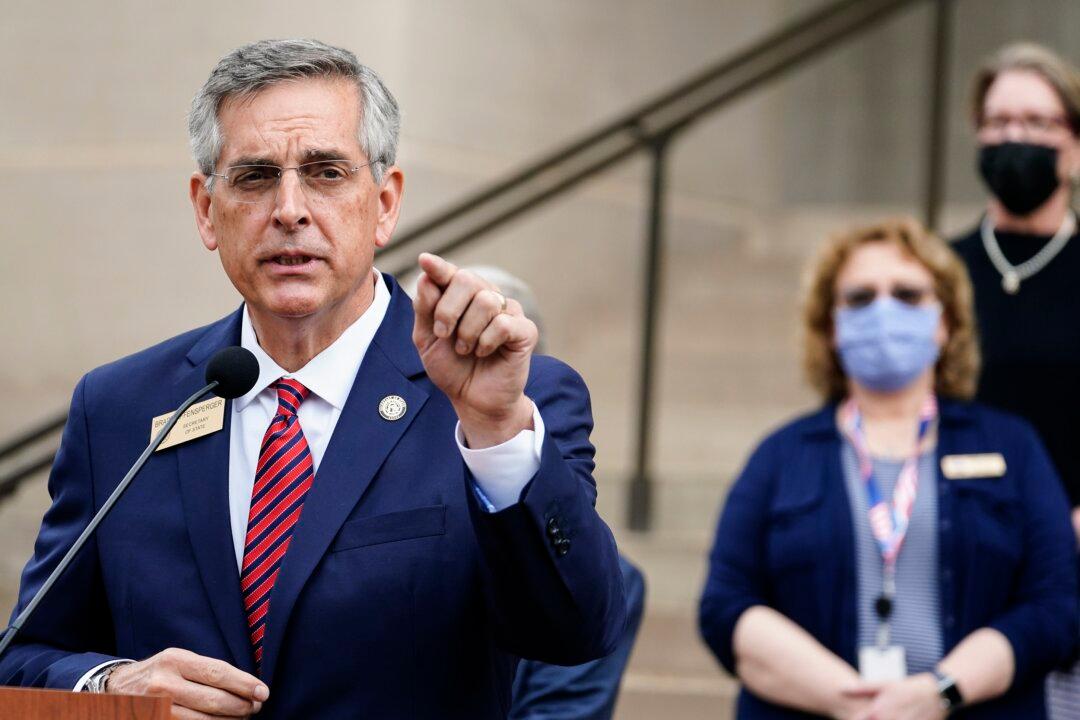

The firm hired by Georgia’s secretary of state to conduct an “audit” of Dominion Voting Systems technology used during the 2020 elections is the same one that previously certified the Dominion systems and also approved a last-minute system-wide software change just weeks before the election.