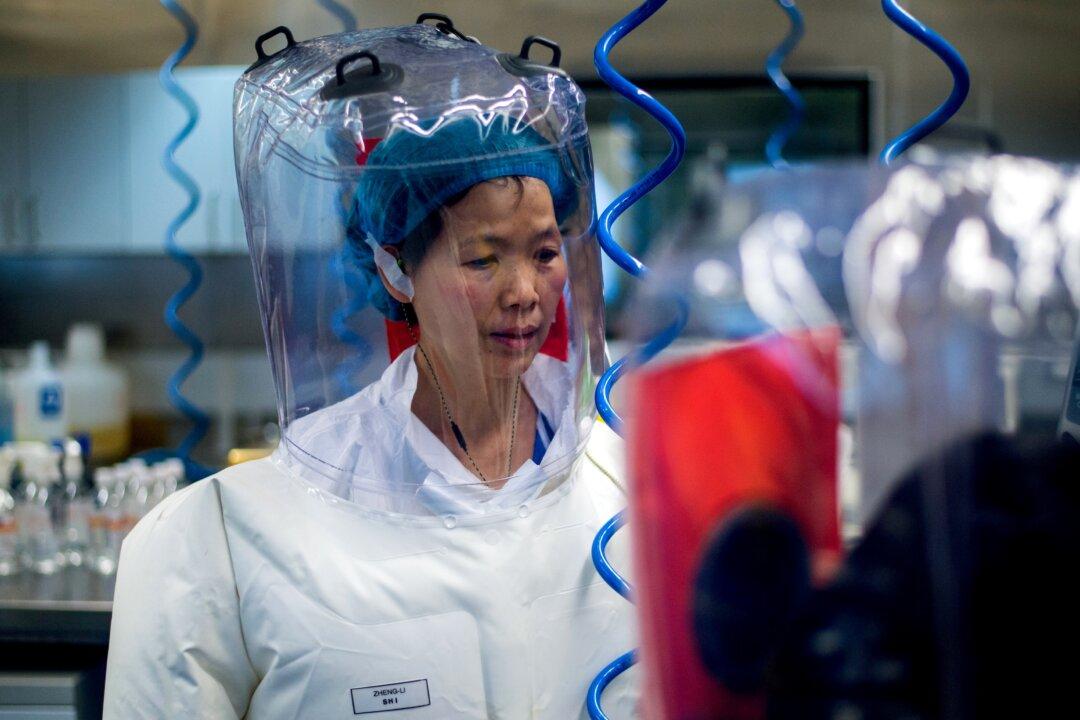

The Chinese regime has said its controversial virology institute had no relationship with the military, but the institute worked with military leaders on a government-sponsored project for years.

The Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) participated in a project, sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC)—a regime-funded scientific research institution—from 2012 to 2018. The project team comprised five military and civil experts, who conducted research at WIV labs, military labs, and other civil labs leading to “the discovery of animal pathogens [biological agents that causes disease] in wild animals.”