Founded in July 1921, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has wreaked death and destruction on the Chinese populace for a century.

Armed with the Marxist ideology of “struggle” as its guiding principle, the CCP has launched scores of movements targeting a long list of enemy groups: spies, landlords, intellectuals, disloyal officials, pro-democracy students, religious believers, and ethnic minorities.

With each campaign, the Party’s purported goal has been to create a “communist heaven on earth.” But time and again, the results have been the same: mass suffering and death. Meanwhile, a few elite CCP officials and their families have accumulated incredible power and wealth.

More than 70 years of Party rule have resulted in the killing of tens of millions of Chinese people and the dismantling of a 5,000-year-old civilization.

While China has advanced economically in recent decades, the CCP retains its nature as a Marxist-Leninist regime bent on solidifying its grip on China and the world. Millions of religious believers, ethnic minorities, and dissidents are still violently repressed today.

Anti-Bolshevik League Incident

Less than a decade after the Party’s founding, Mao Zedong, then the head of a communist-controlled territory in southeast China’s Jiangxi Province, launched a political purge of his rivals known as the Anti-Bolshevik League Incident. Mao accused his rivals of working for the Anti-Bolshevik League, the intelligence agency of the Kuomintang, which was China’s ruling party at the time.The result was that thousands of Red Army personnel and Party members were killed in the purge.

The one-year-long campaign that started in the summer of 1930 marked the first in a series of movements helmed by the paranoid leader that only grew bloodier and broader with time. The mass carnage lasted until Mao’s death in 1976.

While there’s no record showing exactly how many CCP members were killed during the campaign, Chinese historian Guo Hua wrote in a 1999 article that within a month, 4,400 of the 40,000 Red Army members had been killed, including dozens of military leaders. Within a few months, the CCP committee in southwestern Jiangxi had killed more than 1,000 of its non-military members.

At the end of the movement, the Jiangxi CCP committee reported that 80 to 90 percent of the CCP officials in the region had been accused of being spies and executed.

Family members of senior officials were also persecuted and killed, the report said. The torture methods inflicted on CCP members, according to Guo, included burning their skin, cutting off females’ breasts, and pushing bamboo sticks underneath their fingernails.

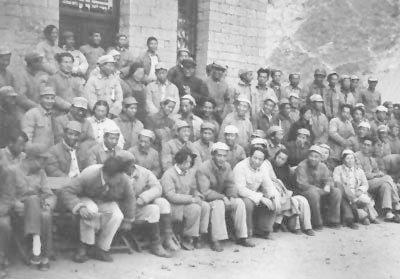

Yan’an Rectification Movement

After becoming Party leader, Mao kickstarted the Yan’an Rectification Movement—the first ideological mass movement of the CCP—in 1942. From the CCP’s base in the secluded mountainous region of Yan’an in the northwestern Shaanxi Province, Mao and his loyalists employed the familiar tactic of accusing his rivals of being spies in order to purge senior officials and other Party members.All told, about 10,000 CCP members were killed.

During the movement, people were tortured and forced to confess to being spies, wrote Wei Junyi in a 1998 book.

“Everyone became a spy in Yan’an, from middle-school students to primary school students,” Wei, who was then editor of state-run news agency Xinhua, wrote. “Twelve-year-olds, 11-year-olds, 10-year-olds, even a 6-year-old spy was discovered!”

The tragic fate of the family of Shi Bofu, a local painter, was recounted in Wei’s book. In 1942, CCP officials suddenly accused Shi of being a spy and detained him. That night, Shi’s wife, unable to cope with her husband’s likely death sentence, took her own life and that of her two young children. Hours later, officials found her and the children’s bodies and publicly proclaimed that Shi’s wife had a “deep hatred” toward the Party and the people, and thus deserved to die.

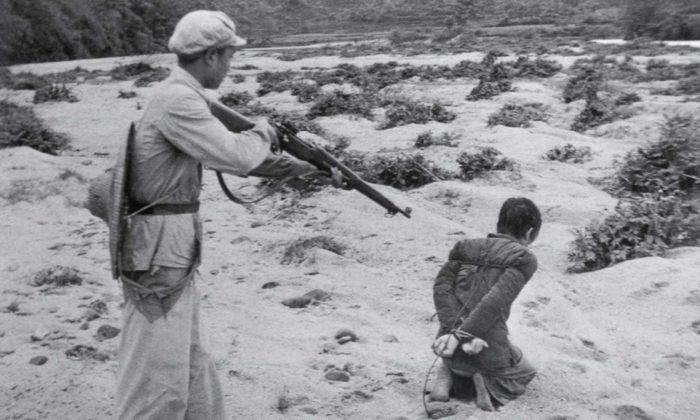

Land Reform

In October 1949, the CCP took control of China, and Mao became the regime’s first leader. Months later, in the regime’s first movement, named Land Reform, Mao mobilized the nation’s poorest peasants to violently seize the land and other assets of those deemed landlords—many of whom were just more-well-off peasants. Millions died.Mao, in 1949, was accused of being a dictator and admitted to it.

Of course, the communists decided who would qualify as a “running dog,” a “reactionary,” or even a “landlord.”

“Many of the victims were beaten to death and some shot, but in many cases, they were first tortured in order to make them reveal their assets—real or imagined,” according to historian Frank Dikötter, who has painstakingly chronicled Mao’s brutality.

The 2019 book “The Bloody Red Land” chronicles the story of Li Man, a surviving landlord from southwest China’s Chongqing. After the CCP came into power, officials claimed that Li’s family had stashed 1.5 metric tons of gold. But this wasn’t true, as the family had been bankrupted years earlier due to Li’s father’s drug addiction.

Having no gold to give to the CCP, Li was tortured to the brink of death.

“They took off my clothes, tied my hand and feet to a pole. They then tied a rope around my genitals and tied a stone to my feet,” Li recounted. He said that they then hung the rope on a tree. Immediately, “blood gushed out from my belly button,” Li said.

Li was ultimately saved by a CCP official who sent him to the home of a doctor of Chinese medicine. Even after suffering severe injuries to his internal organs and genitals, Li still counted himself as lucky. Another 10 people who were tortured at the same time as Li all died. Over the next few months, Li’s close relatives and extended family would be tortured to death, one after another.

As a result of the torture, Li—who was 22 years old at the time—lost his manhood. During the CCP’s subsequent movements, Li would be tortured several more times, costing him his eyesight.

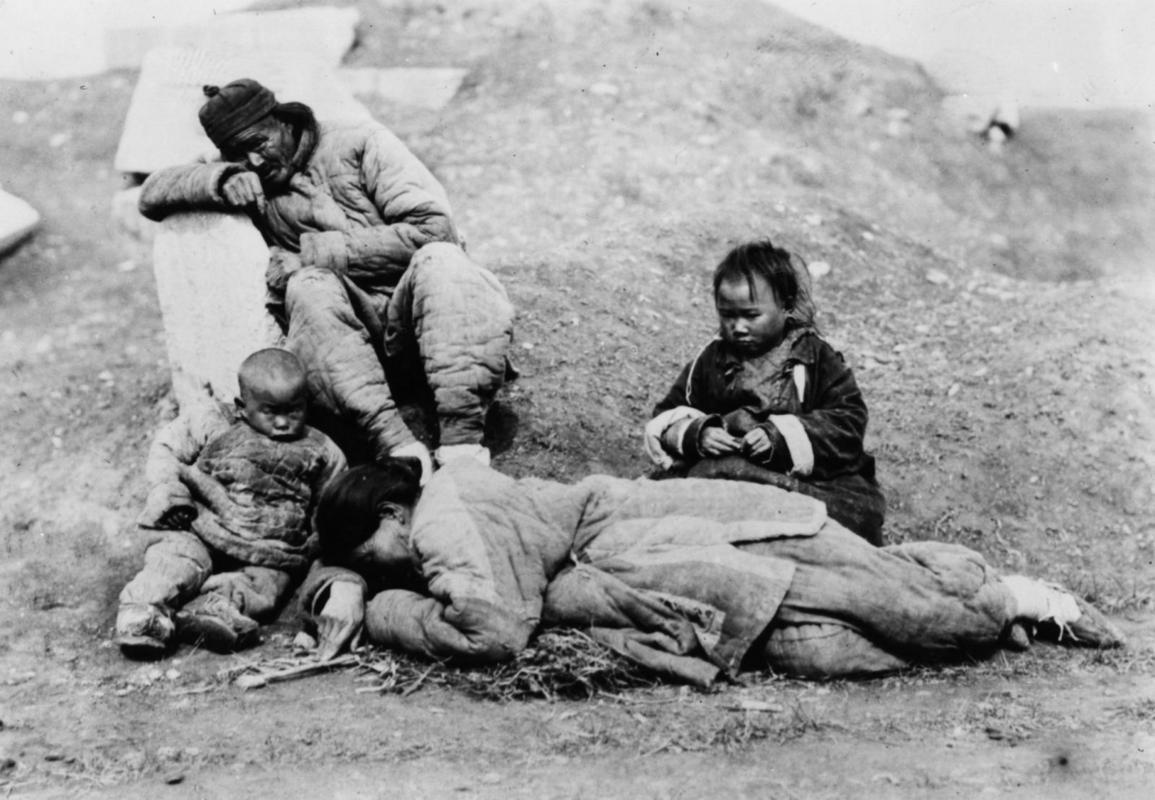

Great Leap Forward

Mao launched the Great Leap Forward in 1958, a four-year campaign that sought to push the country to exponentially increase its steel production while collectivizing agriculture farming. The goal, as Mao’s slogan goes, was to “surpass Britain and catch up with America.”Peasants were ordered to build backyard furnaces to make steel, leaving farmland in severe neglect. Moreover, overzealous local officials who were afraid of being branded as “laggards” set unrealistically high harvest quotas. As a result, peasants had nothing left to eat after turning over the bulk of their crops as taxes.

What ensued was the worst man-made disaster in history: the Great Famine, during which tens of millions died of starvation, from 1959 to 1961.

Starving peasants turned to wild animals, grass, bark, and even kaolinite, a clay mineral, for food. Extreme hunger also drove many to cannibalism.

There are recorded cases of people eating the corpses of strangers, friends, and family members, and parents killing their children for food—and vice-versa.

Jasper Becker, who wrote the Great Leap Forward account “Hungry Ghosts,” said that Chinese people were forced to engage—out of pure desperation—in selling human flesh on the market, and the swapping of children so they wouldn’t eat their own.

Across 13 provinces, there were a total of 3,000 to 5,000 recorded cases of cannibalism.

Becker notes the cannibalism in China in the late 1950s and early ‘60s likely occurred “on a scale unprecedented in the history of the 20th century.”

Yu later interviewed Liu’s surviving family members in the 2000s to verify the story. He wrote in a report: “Liu Jiayuan was extremely starved. He killed his son and cooked [the flesh into] a big meal. Before finishing his food, his family members found his crime and reported him to the police. He then was arrested and executed.”

As many as 45 million people died during the Great Leap Forward, according to historian Dikötter, author of “Mao’s Great Famine.”

Cultural Revolution

After the catastrophic failure of the Great Leap Forward, Mao, feeling that he was losing his grip on power, launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966 in an attempt to use the Chinese populace to reassert control over the CCP and country. Creating a cult of personality, Mao aimed to “crush those persons in authority who are taking the capitalist road” and strengthen his own ideologies, according to an early directive.Over 10 years of mandated chaos, millions were killed or driven to suicide in state-sanctioned violence, while zealous young ideologues, the infamous Red Guards, traveled about the country destroying and denigrating China’s traditions and heritage.

It was a whole-of-society endeavor, with the Party encouraging people from all walks of life to snitch on co-workers, neighbors, friends, and even family members who were “counter-revolutionaries”—anyone with politically incorrect thoughts or behaviors.

The victims, who included intellectuals, artists, CCP officials, and others deemed as “class enemies,” were subjected to ritual humiliation through “struggle sessions”—public meetings where the victims would be forced to admit their supposed crimes and endure physical and verbal abuse from the crowd, before they were detained, tortured, and sent to the countryside for forced labor.

Traditional Chinese culture and traditions were a direct target of Mao’s campaign to exterminate the “Four Olds”—old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. As a result, countless cultural relics, temples, historical buildings, statues, and books were destroyed.

Zhang Zhixin, an elite CCP member who worked in the Liaoning provincial government, was among the victims of the campaign. According to an account reported by Chinese media after the Cultural Revolution, a colleague reported Zhang in 1968 after she commented to that co-worker that she couldn’t understand some of the CCP’s actions. The 38-year-old was then detained at a local Party cadre training center, where more than 30,000 staff members of the provincial government were being held.

While in detention, she refused to admit to doing anything wrong and stood by her political opinions. She was firmly loyal to the Party but disagreed with some of Mao’s policies. She was sent to prison.

There, Zhang suffered horrendously as officials tried to force her to give up her viewpoints. Prison guards would use iron wire to keep her mouth open and then push a dirty mop into it. They handcuffed her hands behind her back and hung a 40-pound block of iron from the chains. Provincial CCP officials even ripped out all of her hair, and guards would often arrange for male prisoners to gang-rape her.

Zhang attempted to commit suicide but failed, which caused prison officials to step up their control. Her husband was also forced to divorce her. By early 1975, Zhang had descended into madness. In April of that year, she was executed by firing squad. Before being shot, the prison guards cut her trachea to silence her. She died at the age of 45.

During Zhang’s detention, her husband and two young children were forced to renounce their relationship with her. Upon learning of her death, they didn’t even dare cry—for fear that they would be heard by neighbors who might report them for bearing resentment toward the Party.

The disastrous movement ended in October 1976, less than a month after Mao’s death.

The legacy of the Cultural Revolution goes far beyond the lives destroyed, according to Dikötter.

“It is not so much death which characterized the Cultural Revolution, it was trauma,” he told NPR in 2016.

“It was the way in which people were pitted against each other, were obliged to denounce family members, colleagues, friends. It was about loss, loss of trust, loss of friendship, loss of faith in other human beings, loss of predictability in social relationships. And that really is the mark that the Cultural Revolution left behind.”

One-Child Policy

In 1979, the regime launched the “one-child policy,” which allowed married couples to have only one child, in a campaign ostensibly aimed at boosting the standard of living by curbing population growth. The policy caused widespread forced abortions, forced sterilizations, and infanticide. According to Chinese Ministry of Health data cited by Chinese state media, 336 million abortions were performed from 1971 to 2013.Xia Runying, a villager from Jiangxi Province who experienced forced sterilization, wrote in a public letter in 2013 that her family requested to postpone the surgery because of her poor health. The local official, however, said that they would do the surgery even if she had to be tied up with ropes.

She began to urinate blood and have headaches and stomachaches after the surgery. Later, she was forced to stop working.

The regime discontinued the one-child policy in 2013, allowing two children. On May 31, it announced that families could have three children.

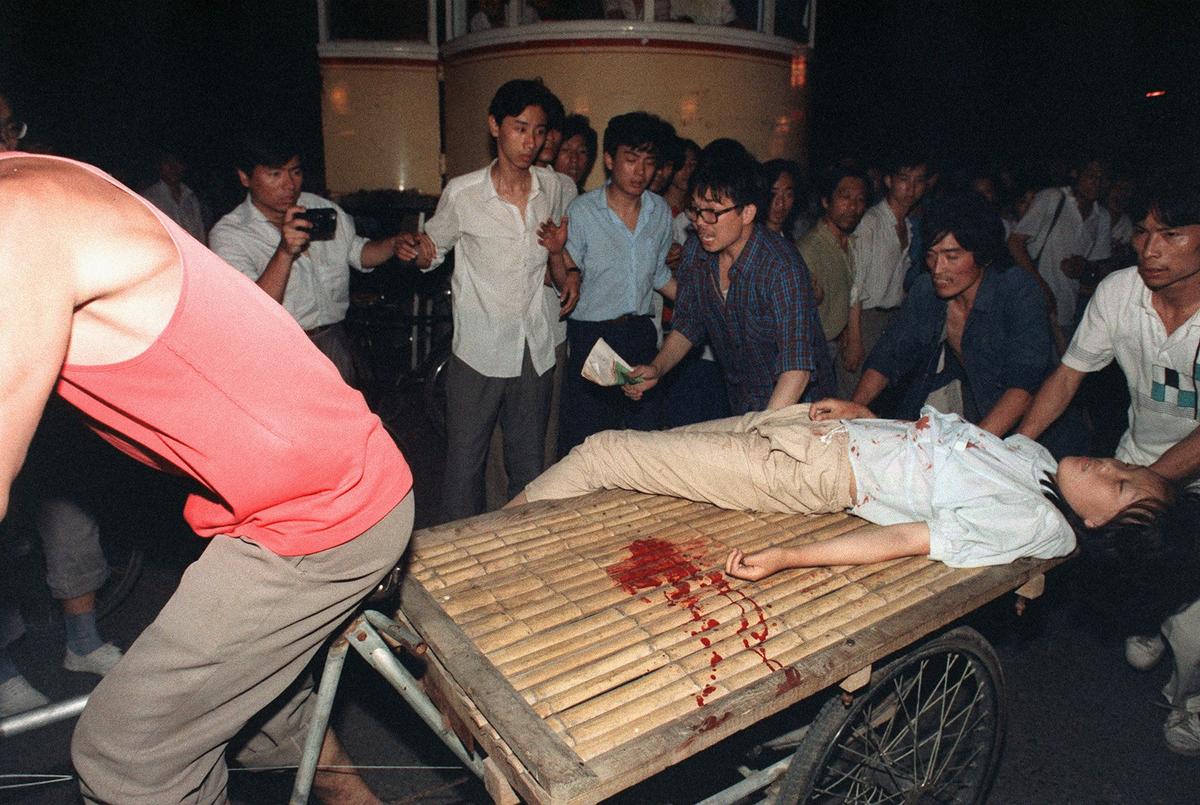

Tiananmen Square Massacre

What started as a student gathering to mourn the death of reform-minded former Chinese leader Hu Yaobang in April 1989 morphed into the largest protests the regime had ever seen. University students who congregated at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square asked the CCP to control severe inflation, curb officials’ corruption, take responsibility for past faults, and support a free press and democratic ideas.By May, students from across China and Beijing residents from all walks of life had joined the protest. Similar demonstrations cropped up all over the country.

CCP leaders didn’t agree to the students’ requests.

Instead, the regime ordered the army to quash the protest. On the evening of June 3, tanks rolled into the city and surrounded the square. Scores of unarmed protesters were killed or maimed after being crushed by tanks or shot by soldiers firing indiscriminately into the crowd. Thousands are estimated to have died.

She was horrified when she arrived at her hospital to find a “warzone-like” scene. Another nurse, sobbing, told her the pool of blood from injured protesters was “forming a river at the hospital.”

At Zhang’s hospital, at least 18 had died by the time they were carried into the facility.

The soldiers used “dum-dum” bullets, which would expand inside the victim’s body and inflict further damage, Zhang said. Many sustained grave wounds and were bleeding so profusely that it was “impossible to revive them.”

At the hospital gate, a critically injured reporter with the state-owned China Sports Daily told the two health workers who carried him that he “didn’t imagine that the Chinese Communist Party would really open fire.”

“Shooting down unarmed students and commoners—what kind of ruling party is this?” were his final words, Zhang recalled.

To this day, the regime has refused to disclose the number killed in the massacre or their names, and heavily suppresses information about the incident.

Persecution of Falun Gong

A decade later, the regime decided to carry out another bloody suppression.On July 20, 1999, the authorities began a wide campaign targeting the estimated 70 million to 100 million practitioners of Falun Gong, a spiritual practice that includes meditative exercises and moral teachings centered around the values of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance.

He Lifang, a 45-year-old Falun Gong practitioner from Qingdao, a city in Shandong Province, died after being detained for two months. His relatives said there were incisions on his chest and back. His face looked as if he was in pain, and there were wounds all over his body, according to Minghui.org, a website that serves as a clearinghouse for accounts of the persecution of Falun Gong.

Suppression of Religious and Ethnic Minorities

To maintain its rule, the CCP regime transferred a large number of Han ethnic people to Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia, where ethnic groups live with their own cultures and languages. The regime forced local schools to use mandarin Chinese as the official language.In 2008, Tibetans protested to express their anger at the regime’s control. The regime, in response, deployed the police. Hundreds of Tibetans were killed.

Since 2009, more than 150 Tibetans have self-immolated, hoping their deaths might stop the regime’s tight control in Tibet.

The regime also uses a surveillance system to monitor ethnic groups. Surveillance cameras were set up in Tibetan monasteries, and biometric data are collected in Xinjiang.