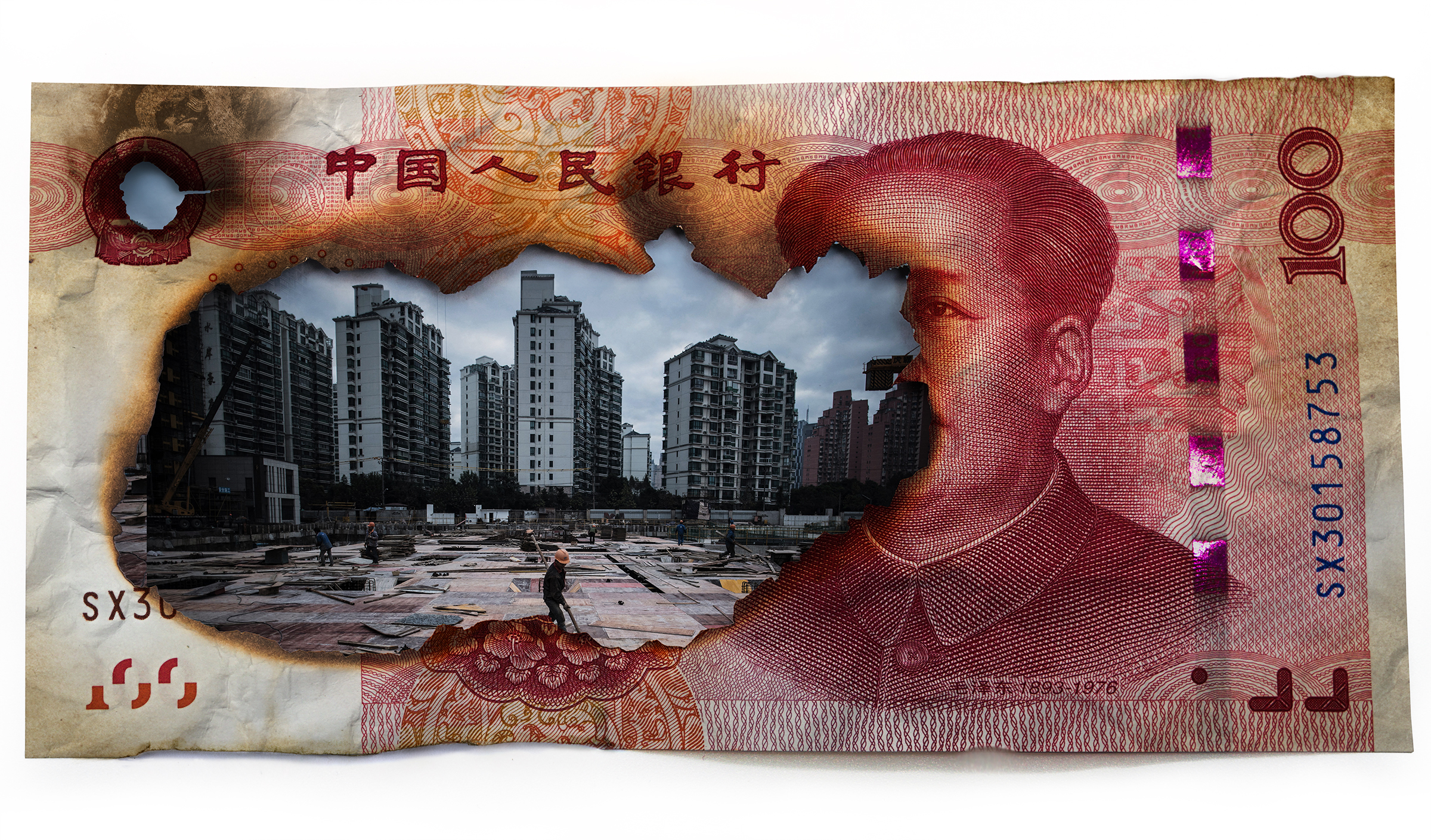

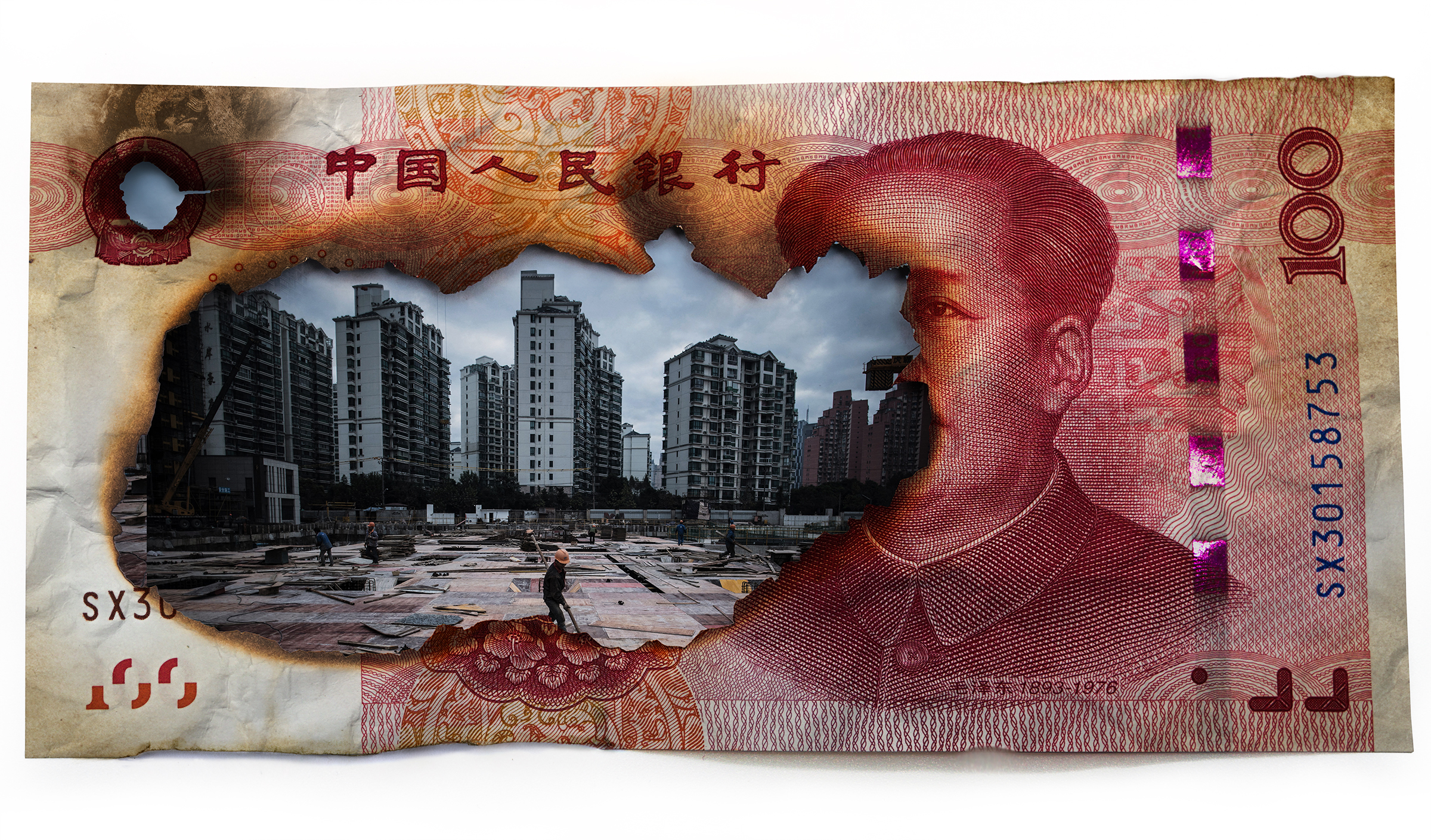

China’s Economy in Grave Danger as Growth Engines Stall, Options Dwindle

Significant perils are facing China’s economy

Illustration by The Epoch Times, Getty Images, Shutterstock

|

Updated:

News Analysis

The world’s second-largest economy is in a world of trouble.