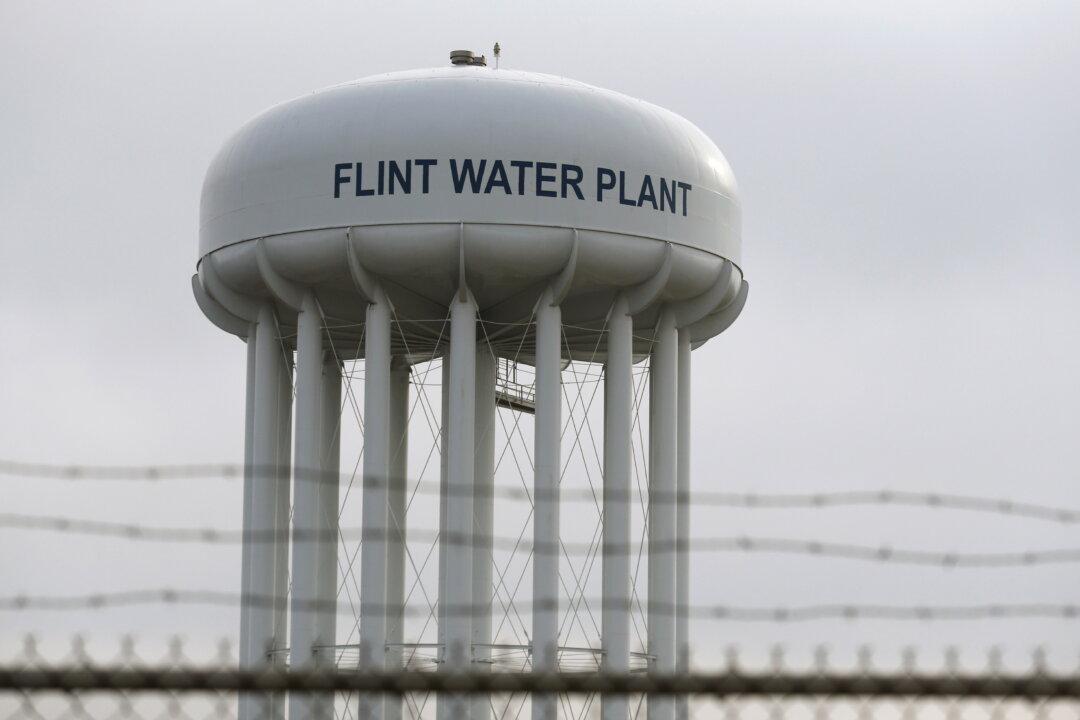

The U.S. state of Michigan said on Thursday that it had reached a preliminary settlement to pay $600 million to victims of the Flint water crisis, potentially closing a chapter on one of the country’s worst public health crises in recent memory.

If approved, the deal would provide the bulk of the funds to children impacted by poisoning of the water in the city of Flint and would rank as the largest settlement in the state’s history, Attorney General Dana Nessel said in a statement.