This year’s May 8 and May 9 marked the 70th anniversary of the Allied victory in World War II over Nazi Germany in 1945. As armies from the United States, Soviet Union, Great Britain, and many other nations liberated Europe from the clutches of the Third Reich, on the opposite side of the globe stood China, in her eighth year of defiance against invaders from Imperial Japan.

But as Chinese Communist Party head Xi Jinping attended the May 9 ceremonies in Moscow, it is yet another year in which the Chinese Communist Party appropriates the sacrifices of another China—the one led by the Nationalists in an epic life-or-death struggle with the warriors of the Rising Sun—in an attempt to play up its own unflattering history.

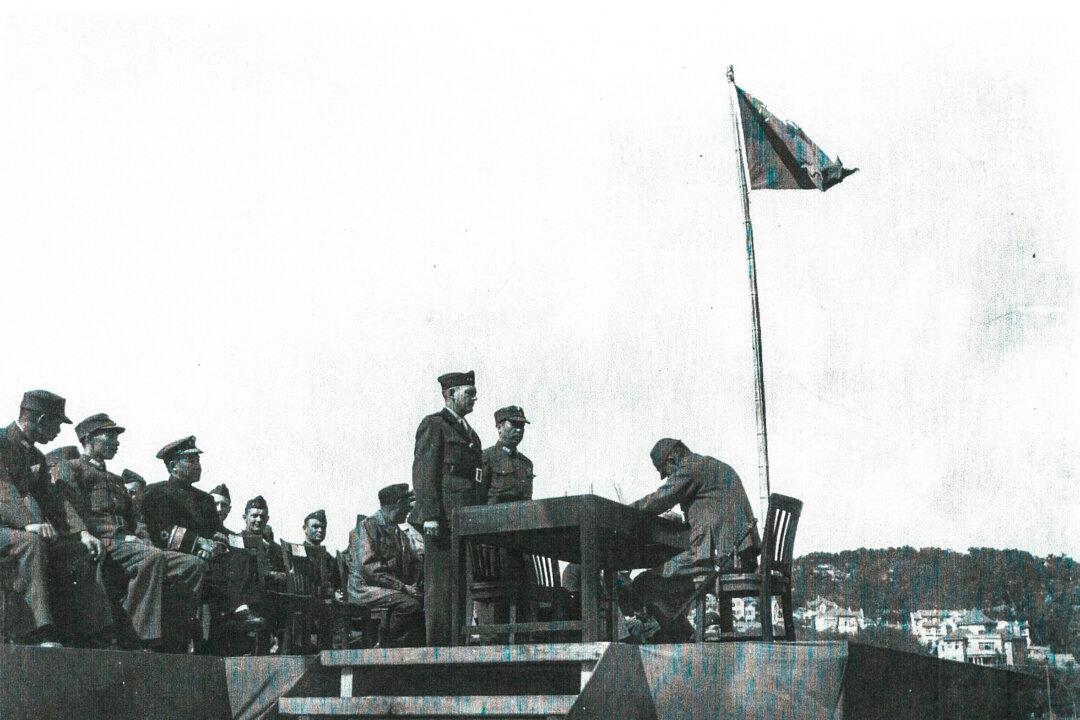

The Kuomintang, or Chinese Nationalist Party, which governed the Republic of China, played the country’s leading role in defeating Japan. At the Kuomintang request, it was the United States that oversaw Japan’s surrender to the Nationalists in China.

It was just several months ago, in September 2014, when the last of the “U.S. China Marines” held their final meeting in Charleston, South Carolina. The China Marines were the American troops who oversaw the surrender of Japan to China, and who were stationed in the country before and after World War II ended.

The China Marines

It was an autumn day on Oct. 6, 1945. Thousands of Chinese civilians gathered on the streets of Tianjin, China. Hanging out of windows and parapets were U.S. Marines. A table stood on the street with a piece of paper on top, behind it was a Marine Corps Honor Guard to the right and a line of senior Japanese officers to the left.