Commentary

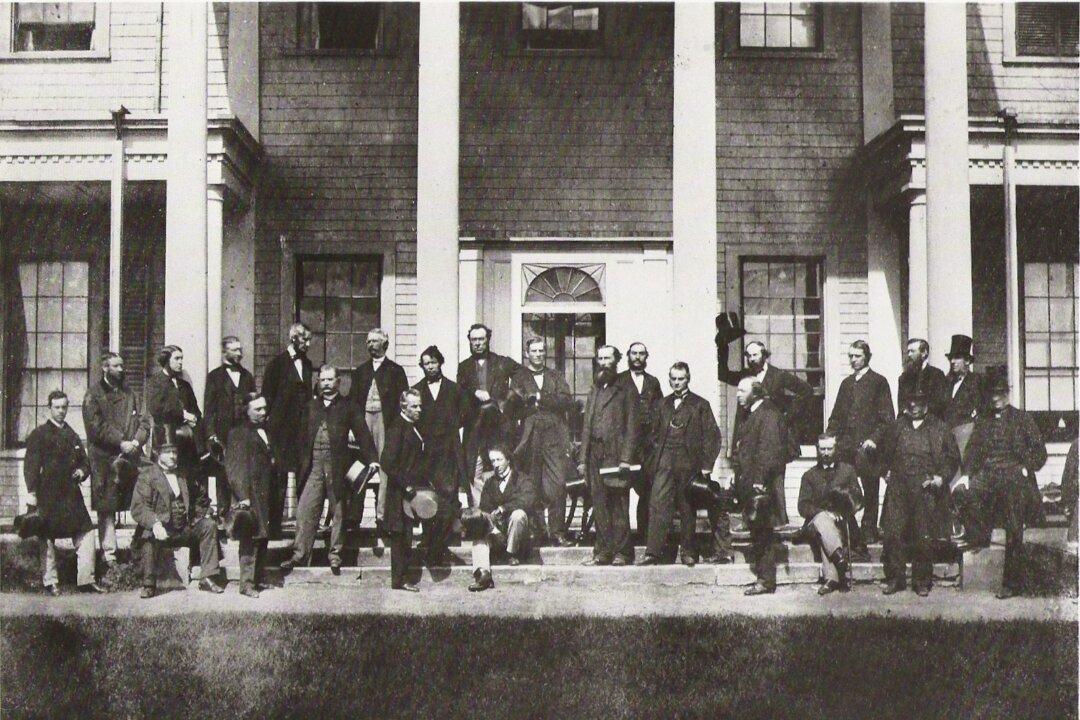

The Fathers of Confederation at the Charlottetown Conference in September 1864, where they gathered to consider the union of the British North American Colonies. Sir John A. Macdonald is seated in the foreground, and standing on his right is Sir George-Étienne Cartier. Public domain

|Updated: