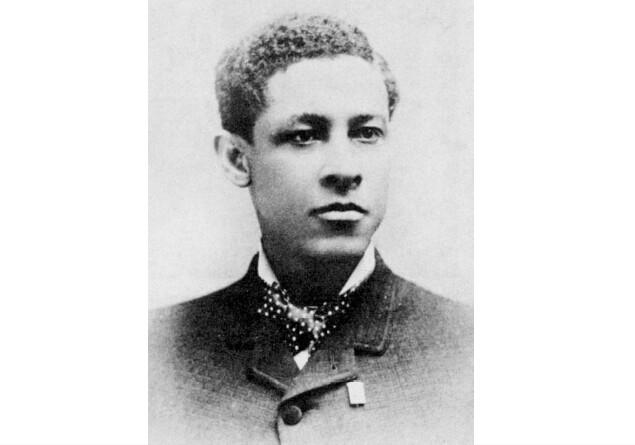

Suppose that I figured out a way to revolutionize the shoe industry. An invention of my own design would double shoe production and cut shoe prices in half. It would provide thousands of new jobs for mostly young or poor people. I could do it without a penny of taxpayer money. Indeed, I faced some major disadvantages to overcome, not the least of which was the fact that I’m a poor immigrant from Dutch Guiana (now Surinam) and my mother was a black slave.

If you met me, knowing what I have just told you about myself, which of the following would you want to say to me?

- You didn’t build that!

- You need to pay more taxes and be regulated.

- Were you motivated by greed?

- Who did you exploit along the way?

- You’re a hero!